The information presented is there to be used and enjoyed but please be sure to

acknowledge the source and author if you use any material.

Thorne Local History Society

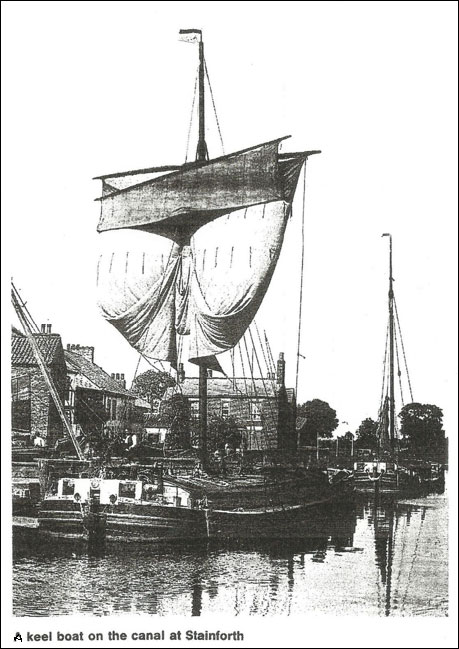

Keelgirl and Captain's Mate

By Evelyn Holt

Thorne and district Local History Society

Occasional Papers No 8

My parents, William Guest Pattrick and Maria Graham, were married on March 18th 1888. Mother was eighteen, and dad was twenty one years old. They had a lovely wedding with coach and grey horses, and were married at Wath-on-Dearne at the Parish Church.

After the wedding, they went to a hotel at Conisbrough called Hill Top Hotel – and it really is hill top because the hill begins at Conisbrough and climbs steadily up for over a mile along the main road until you reach the top where the hotel still stands. After the tea, or Wedding Breakfast, which many keel men and their wives had attended, the newlyweds made their way back to Kilnhurst and were greeted there by Aunts and Uncles who had not been able to attend. Then on to Mexbrough where Dad's keel, the 'Hannah and Harriet' was moored at Waddington's boatyard.

Mother had been servant to the Waddington family since she had left school at 12 or 13 years old. She had finished school early because her father had died while she was quite young, and her mother had married again, to a man called Fred Webb. Now she could not afford the school money – sixpence per week – to send my mother to school. They had to pay for school in the 1800's.

I have heard Mum say that the reason she married so young was that her mother kept having children and did not have time to look after her. She was partly brought up by her Aunt, who we used to call 'fat Aunt Elizabeth' because she was so thin; if we were talking about them, 'thin' and 'fat' distinguished the one from the other.

So Mother’s first voyage on the 'Hannah and Harriet' was her honeymoon trip – and what a trip it turned out to be! They were loaded with coal from Denaby for a mill up the old harbour in Hull. Dad had a Mate with him whom they called Old Tom. I never knew he had another name, as that was the one he was always known by when they talked of him.

Dad and Old Tom hauled the boat down the canal from Mexbrough through Swinton, Kilnhurst and Conisbrough, taking it in turns to

go ashore and pull, then coming back on board to steer and have a meal. That was Mother's job – getting meals ready – as she was no good at steering; she hardly knew one end of the boat from the other. Old Tom used to pull her leg and joke with her, telling her she would never make a keelman's wife if she didn't learn to steer. When they eventually arrived at Doncaster, Dad went ashore to the Horse-Marines' Lobby, and got a horse-marine to haul them to Keadby, so after they had stopped at Thorne Railway Bridge to pick up the mast and leeboards, they carried on to Keadby, where one goes through a lock, leaving the still waters of the canal and into the tidal waters of the Trent.

The next day the boats would go through the lock and moor alongside the jetty waiting for a tug coming from Hull with keels loaded with goods for Doncaster and other places. When the tug reached Keadby, he would guide these keels alongside the top jetty and drop the tow ropes, which the keelmen would haul in and coil on the hatches in neat rings. The tug would then turn around, pick up the keels on the lower jetty, and try to get a good start, well on the way before the tide turned.

On this particular honeymoon day, Dad said he would tow to Hull, which was unusual because Dad hardly ever towed; he always sailed. He often told us that had he sailed, this near tragedy would perhaps never have happened. Dad did most of the steering with Mother sitting in the hatchway, and he pointed out to her the landmarks and the buoys as they passed them. Old Tom had gone for'ard and turned in for a nap. It takes three to four hours to tow to Hull, depending on how many keels the tug has to pull.

Landing at Hull during the afternoon, the tug turns round with the keels and faces the ebb, then gradually steers them stern first towards the jetty at Humber Dockside, or sometimes Minerva Pier. As they were drifting steadily into position a fishing trawler was steaming up river over the ebb, and Dad thought the ebb was too strong for him to make headway into the Fishdock entrance, because the trawler began to swerve nearer and nearer to the keels. As dad was the last keel on the towline and also on the outer side, he was the one that got the terrific bump from the trawler. It gave the keel a sudden lurch and Dad shouted to Mum "Hold fast!" but she didn't know what he meant or who he was shouting to, and the sudden impact knocked her clean overboard. Tom came running aft to see what had happened. Dad jumped into the coggy-boat to see if he could see Mum, and as luck would have it, she had gone under the keel's stern, under the coggy-boat, and she came up at the stern end of the coggy. Dad grabbed her by her blouse and kept hold until Tom jumped into the coggy, and together they managed to roll her into the coggy. Another keelman came to them in his coggy to help. After a struggle they managed to lift Mum onto the Hannah and Harriet.

The tug men came alongside and put the keel at the Minerva Pier. Mother was unconscious; she had knocked her head on the keel rail as she went overboard. All the keelmen and Dad carried her up the pier landing stage as she was so heavy, being wet through. They took her into the Minerva Pier Hotel and sent for a doctor. Dad says she was there two days and two nights. She was soon better, and that was Mum's honeymoon voyage, one that she never forgot!

The Hannah and Harriet did not sink. The tug men towed her across the harbour mouth, on to Sammy's Point, a bank of mud and sand at the harbour mouth. The keel was soon high and dry, and Dad went on the mud to examine the keel's sides and bottom to see what damage had been done. Luckily it was not too serious, and when the keel was re-floated, Dad and Tom took her up the harbour to discharge the cargo of coal. Mum was now better, but still too frightened to go on board again. Without looking for a cargo, Dad brought the keel back to Thorne and went straight to Stanilands' Boat Yard into the dry dock, to see what repairs had to be done. After a bit of nailing, caulking and pitching, everything seemed to be all right. Had that happened today, Dad could have claimed money from the trawler company for damage to the keel and Mother's hotel fees (although I think I have heard Dad say they did it all free). Even the doctor did not charge; Dad gave him a pound and he was satisfied.

While the keel was in dry dock, Mother went house-hunting. She said she did not want another trip like that, but when the keel was out of dry dock, they went up the canal for another load of coal. Mother's Fat Aunt Elizabeth, who lived at Kilnhurst, said she could stay there until she got her nerve back again. Dad made a few trips with Old Tom. Then Mum said she would venture back again, so all was well.

Once, looking around Thorne, Dad heard of a little house in Cobby's Yard. Today it would have been called a cul-de-sac as there were about four houses on each side with no outlet at the far end. It was in the centre of the town, quite near the shops. I think I have heard Dad say that the house was owned by a Miss Harrison, to whom they paid a rent of One Shilling and Sixpence per week. Miss Harrison lived in the first house in Cobby's Yard, the front door being in Bottom Street.

Mum had many trips up and down the canal, but did not venture to Hull many times. She had to stay at home however, because on June 1st 1891, George, my eldest brother, was born. After a few months she was on board again, but Dad said that she was still afraid of the Humber and as soon as George could toddle, she had a rope tied around his waist so that he could not reach the rail and fall overboard. In September 1893, another son was born, my second eldest brother, Arthur. Then again in September two years later a daughter was born. She was called Elsie, and it so happened that she was seven years old before I came on the scene.

During that time, Mum, Dad and family had moved from Cobby's Yard to a larger house on Bottom Street, now Queen Street. I was born in Alma Cottage and lived there for two years. Then we moved to a larger house in Top Street, now renamed King Street. I can remember my life there at the early age of three, all hurry and bustle getting ready to catch a train from Thorne to Hull to board the good ship Hannah and Harriet. That was during the school holidays when my two brothers and sister were at home. George would be leaving school on June 1st, his birthday; in those days they did not usually have to wait until the end of term. As soon as one was 13 or 14, you could leave on the same day, or earlier if there was a job to go to. George was going with Dad as Mate, as Dad could not trust Old Tom.

Dad used to tell us about Tom, whom he once left in charge. They were in the harbour at Hull. It was Saturday afternoon and Dad had no unlading or other work to do, so he told Tom to be on the lookout for any other boat coming alongside, and not to let them damage the keel in any way. They were moored alongside an old coal hulk used to coal the tugs, but hardly used and never moved from its moorings, so Dad knew they would be all right. Dad left Tom plenty to eat for the weekend, then set off for home, which was an hour's run on the train. Arriving back on Monday morning, everything looked quiet, no smoke coming from the chimney, so Dad opened up the hatchway. The fire had not been lit, no food had been touched and everything was just as Dad had left it on Saturday. Dad made his way straight to the for'c's'led where Tom slept. He lifted up the hatch and shouted down, 'Hallo Tom. Are you all right?'. He heard a scuffle, and then Tom shouted in a sleepy voice 'By heck Boss. Have you missed the train. You're back early. I've only just turned in'. He had gone for a lie down after Dad had gone, before having his tea, slept all Saturday afternoon and night, all Sunday and up to dinner time on Monday!

Dad could not trust him, and now that George was growing up, he kept Tom on for a while so that George would not have to do too much as it was a great responsibility being Mate, although he was quite used to looking after the boat. When George was just turned 14, a new bridge was being put across the River Don near the Cake Mill our boat traded to. I remember Dad telling us about the old ferry that carried people across the river from Fishlake and Sykehouse. Now he had the chance to help in bringing the bridge in sections on the Hannah and Harriet. The bridge was to be named Jubilee Bridge. My brother and Tom had to heave a part of it with a wire attached to the main stay roller. Tom let go of his handle, George could not hold his handle now carrying the full weight, and as a result, the handle reversed at terrific speed hitting George on the nose and cheek, cutting a great gash on his face and breaking his nose. He carried that scar always.

After that incident, Dad decided that he and George could manage the boat themselves, so Tom had to find another job, as he could not be trusted to do any serious work.

Two years went by. I was five on April 7th, so after the Easter holidays, my sister Elsie had to start me at school. Not many mothers took their children to school if there were any older ones in the family. I remember my mother giving me a ha'penny to buy sweets on the way to school. We had to pass a little sweet shop nearly opposite the school kept by an old lady called Mrs Wharam. She was also the town’s midwife. She made her own toffee which was called 'Nobby Toffee', but I did not want any Nobby Toffee. I wanted something else. So my sister and I went into the shop and she lifted me up to see what was displayed on the counter. Rows of boxes were lined up full of nice things. I wanted a ha'porth of 'Fat Ducks, Green Peas and New Potatoes'. The ducks were white sweets, shaped like ducks, the peas were small round green sweets like coloured pills and the potatoes were oval pieces of marzipan dipped in cocoa to make them brown. Elsie and I shared them when we got outside, then across the road we went for my first day at school.

It wasn't long before I moved up from the Infants into Class 2. I suppose I was a bit cleverer than some pupils, because George, Arthur and Elsie had to make our own fun, and School was played at more than anything else. They had taught me to write my own name and do easy add up sums. I could read fairly well, and that helped me to be a Class higher every pass-up.

We used to wait patiently for the holidays. We knew we would be able to go all holiday time on the keel with Dad. On one holiday Dad had taken a cargo of coal from Kilnhurst Colliery to the Fish Dock in Hull ready to coal the fish trawlers. We were alongside the trawlers in the late Summer afternoon waiting to unload next morning. The water was only about five inches from the deck-side as we had a good load in. We were all playing about, galloping from one end of the boat to the other, when Elsie caught her foot in a rope. Over the rail she went, head first into the dock. We all screamed, but Dad was watching and he waited calmly for her to come up, and she was doing what Dad had always taught us to do, if ever we fell in – "dog paddling" until we reached the surface. Then she put both hands over her face, took a breath and down she went again. Dad waited for her to come up again, then grabbed her and pulled her on deck. Dad had drilled us, 'dog paddle to the surface, hold your breath, then strike out with hands and legs to the boatside or nearest low object' – not to put hands over the face as Elsie had done or we would sink straight down again. Poor Elsie was none the worse after she was in dry clothes. We teased her, saying she would not need a bath at the weekend.

When I was six, we moved into a house in Ginger Pop Lane. Why it was called that, I never knew, but years later it was re-named Godfrey's Lane. The house was owned by Mr and Mrs Wilson who had a very large house on Top Street, now Fieldside. At one time our house had been a kind of barn. There was a big archway to go through to get into Wilson's Yard, and Mrs Wilson used to spy on us to see if we were getting into mischief. We had loads of room to play, as the yard was massive with more barns and sheds at the end. In later years these barns were converted into a terrace of five houses.

In the centre of the yard was a freshwater pump, supplying the people round about with their drinking water. The pump was a great attraction to the many children who came to play in the yard. It was a very big, iron one. Towards the top it tapered off to a long thin spike. One day Elsie was climbing along the edge of the round trough that caught any spilled water, and she happened to climb onto the spout and so touch the spike top. As she did so, Mrs Wilson came through the archway shouting for her children. When she saw Elise on the pump, she dashed into our house to tell Mum what she was doing. Mum said, ‘They can’t hurt the pump. Let the kids play'' but Mrs Wilson took it the wrong way and went to the Police Station to report it. She alleged that Elsie had sat on top of the pump, so damaging it. As a result Dad was up at Court. Mum was very upset, but Dad said 'Don't worry. I have something up my sleeve. We shall be all right'. When Court Day came, Dad was charged with allowing Elise to sit on the pump top, so damaging the only means of supplying drinking water. Dad asked the Judge if he had seen the pump. He replied that he had not, and Dad asked if the Court could be adjourned for a few minutes until the Judge had seen for himself the pump referred to. In the yard Dad said, 'Your Honour, do you think a child could climb up and sit on top of that spike?'. 'Rubbish!' replied the Judge, who then dismissed the case, leaving Mrs Wilson to pay all the charges. After that, Mrs Wilson was always against us. She even tried to have Dad in court for graining and varnishing the doors in the house. Dad said she would make a laughing stock of herself, as it was for the good of the wood to have them grained.

We were still friends with the Wilson children. Tommy the eldest was a real dare devil and did the most unusual things. He had an old bicycle, a boneshaker, which he lived on. If he came to see us, although he had only to walk through the arch way, it was on his bike; if he went to the outside 'lav', it was on his bike. He could do all the tricks one sees on the stage today – lift up the bike on one wheel, sit on it backwards and ride down the road. He was so clever he earned the name of Bicycle Tommy, a name he kept until he died.

A new frontage was being built to the Police Station, and we used to go to play on the bricks. Later the workmen put all the curbing stones in place along the causeway-to-be. Coming home from school, my friend Ivy Smith and I were stepping from one stone to the other. I was leading and Ivy called for me to go faster. She gave me a push and I fell striking my head on the corner of a stone. I did not know I was hurt until I saw blood streaming down my pinafore. Luckily we lived across the road. Mum washed the blood away, then took me to Dr Parret's who put six stitches in. I still have that scar.

Friends told Mum of a house to become vacant in Kenyon Street. Dad went to see it and we moved in two weeks later, but we were destined not to stay there very long. A Mr and Mrs Chester, with their daughter Ethel, one of our friends, had a house at Waterside. They were going to move to a large house in Orchard Street called Tenby House, quite near to Mr Chester's work. Dad jumped at the chance to live at Waterside, only a stone's throw from the river and Mill. So when I was still 7 years old, we moved yet again. It was a lovely house, standing on its own.

George was by now growing up, and on his days at home with Dad he would tell us about the places he went to in Hull. He used to tell us of a girl he had met, and said to Dad that he would like a keel of his own for when he married.

So, on one of his trips, Dad called at Waddington's Boatyard and ordered a new keel. Oh, what excitement! Every time we went to Mexbrough, we called to see the boat and how big and lovely she was! The Hannah and Harriet was a small keel and carried about 80 tons of coal. At that weight, all the decks were nearly awash: the new keel would carry 120 tons, in those days a big cargo. The cabin was roomy. We could hardly wait for it to be finished in light varnished wood, its buffette in mahogany with looking glass panels, two big bunks, one on either side of the cabin, and large table which would hinge up to be put out of the way. There was a lovely cooking stove, tiny side oven, a recess on top for plates and pans, lockers all round at seat level and again at floor level six more for coal, boots and shoes … plenty of room for all things, everything was so compact.

We had another two or three trips to make in the Hannah and Harriet before the new boat was launched. Dad said I was to christen the keel. We could hardly wait; the time seemed to pass so slowly. Elsie and I were on board on holiday. We had a big red or liver-coloured retriever dog called Jip. When Dad shot a wild duck or rabbit, Jip would jump into the canal and bring it to us. We also had a canary, which lived in a wooden box, whitewashed at the sides and back, painted black on the outside, with a wire front. One day, Mum was cleaning out the cage when she yelled, 'Oh, the bird has got out'. As Dad looked down the hatchway, up flew Toby, across the canal and into the grass on the bank. Dad quickly lowered the sail and shouted to Jip, 'Fetch Toby, boy'. Jip jumped into the canal and with Dad's guidance, nosed about until he found Toby. He picked him up, oh so gently, and swam back to us. We were crying at losing Toby. Dad helped Jip on board. The canary was not even wet, and in a few minutes he was as lively as ever and singing gaily, happy to be back in his cage.

The great day arrived. It was December. We were all dressed in Sunday best, ready to travel to Waddington's to see the new keel launched. Dad had scoured through the dictionary for a suitable name and decided on 'Comity' which means 'courtesy, mildness, kindness'. I don’t think I shall ever forget the hurry and bustle of that day. I was eight and excited. Dad gave me orders to hit the bottle on the keel’s stem as hard as I could, as it must be broken for luck. I shouted, loud and clear 'I name this keel Comity. God bless us all'. Then she slid down the stocks and into the canal with a big splash. Workmen came fussing about me, patting me on the head, saying I had done a real good job for one so young. We did not have the Comity straight away, as so much had still to be done to it, painting, varnishing, fitting out, mast, sails, leeboards, anchors and chains to be added. But she was launched and it would not be long before we took over.

With a new keel and a lovely (rented) house, we thought we were rich. What a walk I had each day. It was a mile to school, a mile back for dinner; no dinners in school then. So in all I walked four miles each day – and more, because, when Dad's keel was at the Mill we used to gallop there and back playing around on the way too. On Sunday, we attended Sunday School in the afternoon, and back at night with Mum and Dad.

At this time George was Mate with Dad, helped out at times by Arthur. When we had been at Waterside just over a year, we looked out of the window and saw George, who had been to Hull for the weekend, walking down the lane with a young woman on his arm. He had got married that morning; what a surprise! He stayed on with Dad for a few months, then found a boat to work, one owned by Forley's " Co. He did not have many voyages as his wife did not like the life at all. She was terrified of the water when the boat was loaded deep and was always dreaming of the keel sinking. So she persuaded George to get a job ashore. They managed to get a little house in Ropery Street, Hull and George went coaling trawlers in the Fish Docks. It was very hard work, among the coal dust in the bunkers all day. He soon began to look ill but he carried on, and they soon began a family – in all seven boys and a girl.

Arthur now took on the job of being Mate, and they made some good trips to Hull and back again to the Cake Mill. When cargoes were 'steady', Dad would see a Mr Rustling and get loads for anywhere up the canal. Once I remember we had a cargo of ready-made coffins from Germany. Arthur hid in one of them, pulled the lid partly on, then started to groan – a horrible groan. Elsie and I went into the hold to see what the noise was. Arthur moaned even louder, pushed the lid off the coffin and waved his hands about. We were terrified for a few seconds – until we realised who the joker was. Then we went for him, but he was through the hold door and up the cabin steps like lightening. Elsie and I could not follow him; we were laughing too much.

Another time our load was sewing machines, again from Germany for Sheffield. After one day unloading there were still about twenty or thirty left for the next day. After tea we went into the hold and, with much pushing and shoving, we got them where Arthur wanted them – all in line. Then he fastened a stout wire through each treadle, pulled it tight so that when he treadled the first one, all the others, one by one, began to treadle like mad. I ran to fetch Mum and Dad who were on deck. We all had a really good laugh; the hold was humming like a bee-hive. Arthur was always a comic, giving us loads of fun.

Arthur, Elise and I enjoyed running on the 'Kelsey'. Its proper name was 'keelson' the backbone of the ship, running from stem to stern down the centre of the keel, made of iron about a foot high and three inches or even less across the top. Elsie and I were quite gymnastic on this narrow beam. We could run from one end to the other without falling off, and with loads of practice could skip, somersault and do all kinds of tricks. When I see the gymnasts of today on the bar which is about four or five inches wide, I wonder what people would have said had they seen us. But we were not so dainty; we had not been shown how to perform with hands and arm movement or how to point our toes to make a pleasing display.

We also had a four rope swing. When the hold was empty, two long ropes were thrown over the beam and fastened. Then the loops were opened to hold a lighter's hatch-board. We nearly always had our dinner and tea on it, swinging all the time, and hardly ever upsetting our tea.

June Fair in Thorne was a great attraction. People came from all over to the roundabouts and shows in South Parade, The Green, the Market Place and Foster’s Field (now the Memorial Park). Arthur and his keel pals – Luther Rhodes, Mizpah and Joe Holt, Percy French and many more – always went to the boxing displays. Fair men used to rig up a tent with a boxing ring inside, then challenge Thorne men to a match, with two or three Pounds for the winner. On one particular day, I wanted to go but all the lads laughed and said I was far too young to see anything like that. Blood would be spurting out all over! I kicked and yelled that I didn't care about blood. At last, Arthur said, 'Well, if you can punch and make Luther’s nose bleed, you can go with us'.

Although he had a hump back, Luther was a big strapping, strong lad. I was small, but in my madness went up to him, held up my hand and said, 'See this finger, see this thumb, see this fist, and here it comes!'. Before I had the last words out, I lashed out. He did not know what had hit him for a second. I caught him right on the nose, and down came the blood. I went to that boxing match all right.

Now that we had a bigger house, Mum and Dad's brothers and sisters used to visit us often. At Fair time we had to put children in our room, aunts in another, uncles with Dad in another. What a full house we used to have! Baking day was a headache, the day before the fair. Our visitors did not let us know they were coming; they just popped in saying 'Here we are'. Mother used to be up early getting the oven hot and the pastry made. All were coal fires and ovens; no electric or gas ones then. As soon as breakfast was over, out came all the baking items. I had to dust and grease the tins, getting them into line for the tarts, etc. It was not long before we had trays of ground rice tarts, jam, lemon curd, buns of every description, sponge cakes, teacakes, spice loaves, currant bread and pies of every kind. There were also flat-cakes, or flattie-cakes which, because they had no baking powder in, always stayed flat, never rose up. Dad used to say, 'It’s a good job the Fair only comes once a year’.

Elsie and I were also the stokers-up, keeping the oven hot. We pared apples, cleaned berries and did odd jobs in between. Mum used to get a large piece of ham, and a very large joint of meat, sometimes pork. We had to see that the pan with the ham did not boil dry, and after the baking was done, to keep an eye on the joint in the oven. It was like cooking for hundreds and thousands.

We were about tired out when it came time to go to the fair. It was a great sight. The Market Place was full-darts, stalls of all kinds – then on to the Green which was packed with the Cockerels, a roundabout with deafening music from an organ with statues of men keeping time to the music with little hammers and ladies dancing and waving flags.

The gypsies used to haggle and fight like mad; we used to keep well away because, when they got really mad, they used to throw knives at each other and many were badly hurt.

Thursday was a special day. A band used to play in Foster's Field, and a balloon ascent was a great attraction. There were pony races, and cycle races which my Dad used to enter – and usually won. He was a keen sportsman, and the sideboard in the room and the dresser in the kitchen were full of his prizes, many of them won before I was born. Once he had won so many that he had to charter a handcart to bring them home. The prizes were beautiful, clocks, a decanter with cut glass bottles, smoker’s outfit, cruets galore, cases of cutlery – we still have many of them today. He loved cycling, and sometimes when he left the keel in Hull, he would cycle home on Saturday, and cycle back on Sunday to see if everything was all right. He would leave home about 7 o’clock and be back for his dinner at around 12.30. In those days it was all corners, the ferry at Boothferry and not many straight roads.

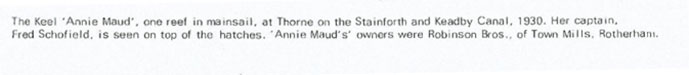

Friday Fair day was the day of the Keelmen's Sports. All the keels in the canal were decorated with flags, up the mast stay, to the top of the mast, with a huge Union Jack or the keel's burgee at the mast head, then more flags down to the top rollers. Keels came from all over to compete in the races. The bridge over the canal and the hauling banks were full of spectators hoping to see their favourite win.

It took all morning getting ready for the afternoon races, sculling races in coggy-boats for keelmen, and also one for the women. As I grew older, I once entered sculling with one oar and came first winning a silver vase with three holders which I have today.

The Greasy Pole was the highlight of the day. About 25 feet long and attached to a crane on a dais from the Canal Company Yard, it stretched over the water, tapering slightly upwards. It was thickly covered with soft soap and tallow, and on the end over the canal was a flag. The men tried to walk the length of that pole and grab the flag. Many went only a few feet before they slipped off. After many attempts, as the grease got cleared off, someone would take a good many steps, and even manage to get to the flag – but to win, it had to be pulled from its socket.

On Saturday, most people made for Foster's Field where the band was playing again, and field sports such as running races, egg-and-spoon races were held. Last of all was a marvellous firework display, exploding with hundreds of coloured stars. It was, 'Ooh, how lovely. Isn’t that beautiful' and the oohs and aahs got louder as the bangs exploded. After the fireworks we all went back to the fair, throwing our pennies to win a goldfish.

Our weekend visitors usually went home next morning by train – some on Dad's side to Ashby, Scunthorpe, Mum's to Mexbrough, Kilnhurst or Swinton Common. The busy week was over; soon everything would be back to normal – Dad and Arthur back on the keel, Elsie and I back to school.

1908. Elsie would be 14 in September, time for her to leave school. She had no idea what she wanted to do. Most girls went into service, but Elsie stayed at home for a while to help Mum do the housework and help in the garden.

Mum was friendly with a Mrs Trimingham. They had a clothes shop in The Green. They had three girls, one called Evelyn after me, the next Elsa with an A at the end after Elsie, and the youngest Greta. She was a lovely little girl, and almost lived with us. Mrs Trim (as we nicknamed her) used to go out daily on her bicycle with two large suitcases, selling things from the shop. She did pretty well too, and sometimes sold all the clothes that were in the cases, with orders for more. It was often late in the afternoon when she arrived home, so she asked Mum if Elsie could tidy up the house, and get the meals ready for the girls and Mr Trim. So Elsie became her part-time maid. Later she heard of people in Doncaster who needed a maid. They had a fish and chip shop, and wanted Elsie to help in the house and look after their little boy. She did not stay there long as the work got harder and harder. They soon had her working in the shop, helping with the peeling of potatoes and cleaning the fish, as well as the housework. So Mum told her to pack up and come home.

We had lived at No 2 Quay Road for about two years. Then the house next door came up for sale. Mr Aukland died suddenly and his widow said she couldn't live there alone. The house was far too big. She had mentioned it to a Mr Tom Gravil, a friend of the family, and he had advised her to sell it by auction. Dad told Mr Gravil that he would very much like to buy it and Mr Gravil said he would do all he could to help, but it would still have to go through the auctioneer’s hands.

It was a lovely big house – four bedrooms, two front rooms and a kitchen, and a small cottage adjoining that made the house even larger. There were stables, cowhouses, haylofts, pig styes, poultry sheds with a large garden and orchard. Dad went to the auction and became the owner of the house for £350. We moved in early in 1913, and Dad soon had a nice name for it – Riverville – and that is its name today. Dad made improvements – we had all the old windows with sixteen panes taken out and ones with four large panes put in. A blank one in the centre was replaced by a four pane window. I remember Mum saying we would never be lonely now that we had a big house, and how right she was! Hardly a weekend passed without some of Mum's or Dad's relatives coming to us.

In February 1914 when we had been in Riverville for just over a year, Dad had to go to Immingham for a cargo, and Mum went for a trip with him, leaving Elsie and me at home. That night a terrible storm arose. As night came on it got worse, until it turned into a hurricane. We were terrified. We dare not go out; we really thought that the house would be blown down. We sat huddled together all night on the sofa in the kitchen. During the darkness a great gust of wind shook the house and we heard a loud bang on the house top; we fully expected it to fall in at any moment. I began to cry and kept asking Elsie if Mum and Dad would be safe. She assured me that they would have got to the docks in Hull before dark and that they would be all right. So we had to wait patiently until morning. Eventually it began to rain, and did it rain! It came down in sheets, battering on the windows and flooding everything. But the heavy rain checked the wind and calmed it down to a steady gale. When daylight came, we peered through the glass panel in the kitchen door. All we saw was a mass of branches, and water everywhere. The verandah that was in the back yard had been broken by the old pear tree which had been uprooted and blown against it. We were still cleaning up branches when Mum came home. We were pleased to see her! Dad had been worried about us and had sent Mum home by the 9 o’clock train.

Later that day we were to hear that Dad's brother, Uncle Jack had perished in the hurricane. He was Mate on a tug called 'The Clansman' which had been called out to a ship in the Humber off Spurn. Hugh waves had capsized the tug, and she had sunk with all hands lost. It was said that Uncle Jack was found with his life belt on. He was just alive, but died before they got him to Hull to the doctor. I remember them bringing his coffin to our house, and putting trestles in the front room to hold it. I used to shudder each time I passed that door to go upstairs for many months, perhaps years, afterwards. It was the first time I had seen death.

A friend of Elsie's, Ethel Whitehead, was in service in Halifax. The people who employed her went abroad every holiday, which gave her the chance to come home regularly. She said she could get Elsie a good place in Halifax and they would be company for one another. Elsie decided to go. Ethel had a brother called George who was learning to be a butcher in a small village on the way to Rotherham called Hooton Roberts. When the girls were at home, all three got together and usually came to our house. Elsie and George became great friends. When the 1914 war started, George Whitehead was called up to join the army – he went into the KOYLI – and he wrote to Elsie keeping up the friendship. It eventually grew serious; letters and postcards arrived nearly every day. When he went to France he sent the most lovely silk cards, which Elsie had mounted and framed.

I left school in 1916, when I was fourteen. The war was on and Mum was nervous about being left alone so I stayed at home. Elsie was still at Halifax and Arthur used to stay at Hull whenever he could as he had a girlfriend there. We guessed it wouldn't be long before he was married. It would be my turn next to be Mate on Dad’s keel. It came sooner than we expected. Arthur got married and took a lighterman’s job in Hull until Dad could get him a keel of his own. He soon heard of an iron keel being built by Scaife’s of Beverley for a man who then found he could not get the money to pay for it. Mr Scaife knew Dad and gave him the chance to buy the keel instead. It was nearly ready for launching. When all was finished, Dad and Arthur went to Beverley for the new boat, which Dad had named 'Medina'. She was even bigger than the Comity, and Arthur and his wife were to work it and pay Dad what is called 'thirds', that is a third of all the cargo payments. She made some big profits, as she carried over 160 tons. When trade in cattle cake or locust beans for the Mill was scarce, Arthur took cargoes of coal or other items to Grimsby or Immingham or up the Goole canal to Leeds.

In 1916 George Whitehead was wounded, and when he came out of hospital on leave, he asked Elsie to marry him. The Wedding Day was fixed for Boxing Day 1917. Mother wanted them to wait for the New Year, but George said it was near enough to the New Year. So Elsie gave up her servant’s job in Halifax, and stayed at home for a few months getting things ready while George had to go back to Aldershot until he was discharged. While she was at home, Dad persuaded Elsie to go with him as Mate on the keel until George came back.

Mrs Trimingham still went on her rounds with clothing, and called in to see us regularly. On one of her visits, she asked Elsie to help her remove from the shop house to one on Bottom Street. The business was doing so well that the rooms in the shop were needed for storage. Elsie helped to clean, paper and paint the new house between her trips to Hull with Dad.

George came home from Aldershot. At the time we had Dad's sister Aunt Betsey and Uncle Joe from Scunthorpe staying with us for the weekend. They invited George and Elsie to go back with them for a week's holiday. The day they came back, Mrs Trim was at our house, telling Mum about a young woman at Rawcliffe who wanted to give away her baby boy. As she would be always seeing him, she did not want anyone in Rawcliffe to have him, and so she had asked Mrs Trim if she knew anyone who could give him a good home. Mum said ‘No’ at first, but Elsie thought it a great idea and said 'Yes. Bring him to me; I will have him'. Mrs Trim said that she would not be seeing the young woman until the following week; she would tell her then.

Meanwhile, Uncle Joe wrote saying that he had got George a light job in the offices of the Frodingham Iron and Steel Works, where he was foreman. So off went Elsie and George to live with Aunt Betsey and Uncle Joe until they could get a house. One day Mum and I were interested in seeing a lady in the lane; she was pushing a very big boat-shaped pram and, as she herself was very small, she kept peering past the hood, first on one side then the other. None of us knew her, so when she got near, we went out onto the path to see if we could direct her to where she was going. She came across the road. 'Do you know of a Mrs Pattrick who lives at Waterside?' she asked. My Mum said, 'I am Mrs Pattrick'. 'Well, I have brought the baby Mrs Trimingham told you about'.

What a surprise! We all went into the house and had a look at the baby she was giving away, the one Elsie was to adopt. We had no papers to sign, no formalities – she just handed him over with a few clothes, a feeding bottle and a little food, his birth certificate and the pram. She promised to send ten shillings a month to help with his keep. Then after a cup of tea, she had to hurry to catch the train for Goole where she could take another for Rawcliffe. I remember Mum saying that Elsie would be lucky to receive any payments. How right she was! I think we only got one; then we heard she had gone to live in Middlesex, and that was the last we saw or heard of her. We wrote to Elsie saying the baby had come. But another surprise! She wrote back saying she could not manage him now as she was having a baby herself; would we take care of him until she was well enough to take him?

We got to love him like one of our own. He was just two months old with dark brown eyes; his name was Eric but neither Mum nor Dad liked that name, so he became Billy Pattrick after Dad. Mum and Dad saw no reason to have him legally adopted; they said he would always bear our name, but as the years went by, and I grew older, I begged them to see someone who would tell us how to make the adoption legal. Dad went to the solicitors and came back saying that it would cost us £5. To Dad that seemed a lot, so everything stayed as it was. Billy was still Billy to us, but Eric Lister to people who were to know him in later years.

And now, with George, Arthur and Elsie married and away from home, I began my life as a Keel Girl and the Captain's Mate, at the age of nearly fifteen. Dad said to me, 'How long are you going to stay as Mate with me? George was with me nearly five years, Arthur three, Elsie one year – so now it's your turn'. 'Well Dad', I said, 'You have worked and brought me up for over fourteen years, so I will try to repay you. I will help you all I can for fourteen years'. The years rolled on, and I was Dad’s Mate for nearly eighteen, so I think I really and truly earned the name of Captain's Mate.

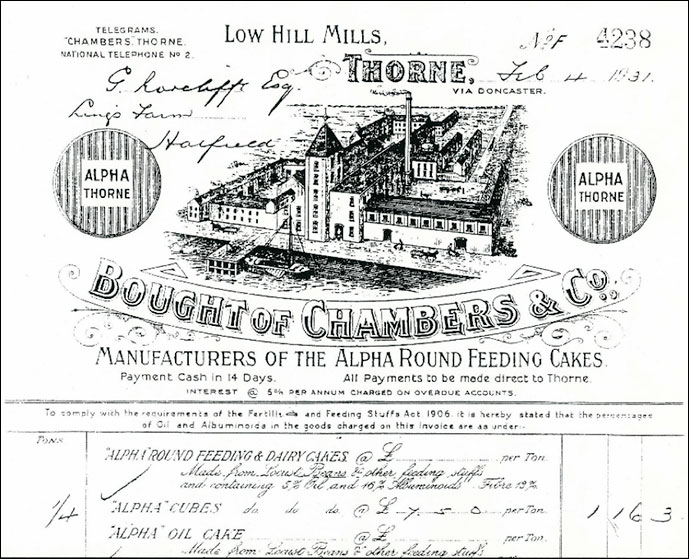

All the keelmen and keelboys, all the lightermen and dockers called me 'matey'; they always had a greeting for me when we arrived in the docks or Old Harbour. Most of the Mill men used to shout to me because I had to help with all the loading and unloading at Waterloo Hill where we traded regularly. They used to shout, 'Get your arms ready for the cakes'.

The cattle cakes came down from the spectacle on a square board, a quarter of a ton at a time, and all in threes. We had to lift the three cakes and stow them in rows along the keel hold, the stacks getting higher and higher with each three cakes. Lifting and stowing was an arm-aching job, as we had to keep a continuous movement. After about twenty tons, my arms would hardly move.

But it was a great life and I enjoyed every bit of it. Dad was so good; he hardly ever lost his temper; he didn’t drink or smoke and I don’t remember him use any kind of bad language. He was a proper gentleman.

The trade to the Cake Mill at Thorne kept us in fairly regular work. Cargoes were plentiful, because, if we didn't have one for the Mill, Dad used to see Mr Rustling who was a Ship's Husband – one who chartered cargoes for different places. He would arrange a quick trip to Doncaster Mills, or Mexborough, sometimes Leeds or Sheffield, bringing a load of coal back to Hull. We went to most of the mills in the Old Harbour, as they nearly all dealt with cattle cake and meal. It was a fair trek up the harbour as keels and lighters were always moored at the mills on either side of the harbour and so it was all twists and turns, and bridges galore. No sooner were we at one bridge than another one came in sight, and with a strong tide running, it was a work of art pushing from one side to the other, popping fenders in, if we were running into a moored keel.

The keelmen and their lads used to wave and shout as we passed and, if they were loading nuts or anything else good to eat, they would throw across handfuls for me. Once we were loading locust beans for a cargo boat in King George Dock and I went sculling about in the coggy while Dad was loading. Another big cargo boat was unloading in a nearby bay and the dockers shouted to me to come alongside. I sculled over, and they threw a massive bunch of bananas into the coggy. Before I could shout 'Thank you' and scull away, they had half-filled the coggy with bananas, mostly still green, but by the time we arrived back at Waterside, they were almost ripe. The kids there had a treat; we were eating bananas for over a week!

The locust beans we used to bring to the Mill had a lovely smell and were good to eat. People used to walk from Thorne to the Mill to get some. Some of the beans were very sweet and sugary. When we had a load of them, we sometimes had to stay at Rawcliffe Bridge on our way up-river. We usually managed to get there around high-water. Then all the Rawcliffe children would stand on the bridge shouting, 'Throw us some 'bungy''. Bungy was the nickname for locust. I used to shout back 'We haven’t any'. 'Oh yes you have. We could smell it as you came from Goole. So I had to satisfy them, and throw handfuls onto the bridge. Then what a scramble there was! Some were shouting, 'He's got more than me; throw us some more'. They used to love to see our boat coming up the river.

Dad’s keel was the only one to use the River Don, otherwise known as the 'Dutch River'. I understand it got that name from the people who created and channelled it in the days of Vermuyden. Sometimes when the Mill wanted more than one load of Locust, Dad would try to charter another keel but not many would take on the job as the river was so treacherous and dangerous. Hundreds of tons of rock stone had been put on the banks of the river to protect them, but the big tides soon washed the mud away then the stones slipped down the bank into the river bed where they formed what we called 'stone-heaps'. Dad knew every one of these and was always careful not to anchor near them.

Sometimes, if we landed at New Bridge when the tide was about to turn, Dad would put me ashore with a line and 'seal'. A seal is a belt about six inches wide made of canvas or sail cloth which fits around the chest and shoulders, with both ends fastened to the line. I would have to put this on and pull the boat, as hard as I could. Once we got moving it was not too bad, walking along the river bank, although you had to throw the line over the willow trees and dodge the tree branches. Dad would be pushing with a boat-hook and steering at the same time, until we could get to the end of the 'long rack' where it was safe to anchor. The long rack was a straight stretch of the river about four miles long, and we had either to stay at New Bridge where the rack began, or if we thought we had the time, to carry on to the end before the tide turned. Just beyond it, all the corners and bends came into view. I remember once when Dad had put me ashore to haul by hand, we had to pass the big farm house where people called Stones lived. Mr Stones spoke very broad Yorkshire. When he saw me, he waved and called to his wife, 'Tha'd better bring th'owd grey mare from'pt staybles an' tether her to this poor lass pulling this boat'. I had to stop pulling to have a good laugh with them. We managed to get to the end of the long rack and drop anchor and tie up to the willow trees. Then we could walk home from there, but we had to be back again for the tide. It only ran up for two hours, and down for eight hours, so we had to be ready again for the turn of the ebb, to get the boat to Waterside.

On big tides, we raced up the river at great speed. Dad had to be for'ard with a boat-hook while I had to be at the tiller swinging it across the deck, first one way and then the other to get round the stone-heaps. One had to keep clear of the tiller because if it caught a stone-heap it would knock anyone overboard. I had that misfortune once, when we were coming up the river. The tide was so strong that Dad thought it best to go stern first; then he could keep the keel steady trailing the anchor. The result was that we went stern first into a stone-heap, and the tiller banged over at a great speed, knocking me clean over the rail. Luckily I grabbed the tiller and hung on, while Dad ran aft to pull me aboard. Had I fallen, I would have had a wet bath.

But once through the Jubilee Bridge, we were all right for reaching the Mill. Sometimes we did not have briggage and had to drop anchor in a hurry, then wait for the tide to turn and lower, until we could get under the bridge. If the cargo was needed urgently, we had to take a line ashore, fasten it securely to a tree and then wind the other end to the sheet roller and heave our way under the bridge. This was a very slow process, as we had to take one line along, while the other held the boat. I was pleased this did not happen very often. Sometimes the mil men would come and help to pull, and that made it easier.

As soon as we reached the Mill jetty and moored, we could heave a sigh of relief. Work was still to be done however, for as soon as we were moored, the boathooks and ropes, etc. were all lain on the decks, the hatch covers all neatly turned back and hatches taken off, so that work unloading would start straightaway.

The Mill at Waterside had a jetty jutting into the river about ten or twelve feet long. This we moored to until we were wanted to unload. Then we had to move away from the jetty and under a spectacle that ran from the upper rooms of the Mill, over the road and partway over the river. The full length of the spectacle was a moving belt. At the end of the river was a roller with a chain that used to pull up the bags or cakes, through the trap doors. They were laid on the conveyor belt. Locust was laid on the belt in the bags, to be emptied down a chute by a man who put the empty sacks into another sack which was brought back to the spectacle end and thrown through the trap doors into the keel. He would shout, 'Below there!' and Dad and I would move away from the trap doors, then down would come the bags 'Thud'.

I was the filler of those bags as Dad could not always get a man to be a 'filler out'. So I had to be a workman, filling each bag by the time the chain came down again. If we did get a workman, I still had to be there, holding the bags open and shaking them to get in as much as we could. It was the same with coal, only instead of bags there were large-mouthed baskets. Once we had a cargo of coal for Lee-Smith's Mill up the Old Harbour. Some of the mill men were on strike and the coal was badly needed, so Dad asked me if I would help fill out. So I went on top of that ninety tons of coal, and was it hard work digging down! Once you got to the shutts it was not too bad, but digging down from the hatch top was awful. When a big hole had been made, it got a bit easier, but then the top coal would come sliding down again and all the loose coal had to be dug again. It was terribly hard work. I used to think we would never reach the bottom. After that it was just shovelling all the time; one had an even bottom to shovel on so it was quite easy as the coal kept sliding down and there was just the loose coal to shovel up. It took us three days to unload the ninety tons, as the crane man kept leaving us to see what was happening in the mill. He was very erratic heaving up the baskets as he was not used to crane work.

After that, Dad went to Waterloo Mill to see if they had a cargo for home; we had to go to Alexandra Dock for some rape meal but they were not ready for us, so Dad took me in the coggy round the large lockpits and said he would show me how to stick 'flatties'. Flatties were small flatfish, like plaice only much smaller. They used to swim up the walls of the lock pits; when no ships were expected the locks were left at dock level and we could scull all round and see the flatties just below water level. Dad tied an old fork with fairly long prongs onto a piece of wood about four feet long and told me to scull the boat close to the wall side, then to let it drift gently along not making a sound. Then he would make a sudden dart at a flattie with the fork, and with a sharp movement flick the flattie into the boat. We got about ten on our first trip.

Back on board, he showed me how to clean them by pulling off the heads and clipping off the fins and tails. After washing and cleaning they were ready to fry or cook with parsley sauce. They were delicious being salt-water fish. I did not do very well on my first try, as I flicked them too hard and missed the boat, but after a few attempts I soon learned to jab them properly and became quite a dab hand at it.

I used to do quite a lot of fishing when we were loaded low in the water. I had three or four lines set around the keel and caught many good fishes. I hated to catch eels; they used to tangle up the lines and the slime off them was terrible. They curled round my hands and arms and to get the hooks from their mouths was a problem. One had to get just below the head in between the first and third finger, with the middle finger over the top. Then one could hold them without them slipping; otherwise they just slipped through the hands and fingers. I kept them in a large bucket until we got home as Mother loved them and made jellied eels or fried them or stewed them; she enjoyed them in any way. Manys the time I lost four or five, because they could rear themselves up and slide over the bucket edge. I had to tie a bag over to keep them in.

One lovely day I had been sculling around, picking up fire wood and I had a few flatties in the boat. I sculled up to a cargo boat thinking to get a few oranges or something and I happened to glance where the keel was. Dad had moved away from the boat we had been alongside, and I saw him waving for me to come in. I turned the coggy round quickly and the oar slipped from the hole. Over the side I went – but only partly. I managed to keep hold of the side of the coggy. My head and shoulders however were hanging over the side and partly under water while both my feet were still in the coggy. I could not push myself up, no matter how I tried; I just had to wait until help came. The wavelets kept dashing over my face and head. I couldn’t hold on much longer, but a lighter man had seen me and he jumped into a keel’s coggy and came to my rescue. Poor Dad was in tears when I got to the boat, as he had had no coggy to come to me. I was none the worse, however; it was only one of my escapades.

One that might have been a tragedy happened as we went with a lovely fair wind from Thorne to Hull. As soon as we had briggage at Jubilee Bridge we sailed down the river to New Bridge. We had just briggage there and so sailed on towards Rawcliffe. The Bridge there was very low, an old wooden structure, so we had to wait for the ebb to lower enough for us to get under. None of them were opening bridges. Dad said, 'put the kettle on, and we'll have dinner while we are waiting, and I will lower the mast'. The sail had been lowered already. So I went down to the cabin to get the meal ready, when all of a sudden the kettle flew out of my hand and everything was shivering. I tried to get up the cabin steps, but they were edged with brass and each time I tried to step on them, I was thrown back on the lockers. Whatever had happened?

I looked up the hatchway and could see sparks, flames and flashes up and down the rigging. Then a big bang; the mast had fallen down. When I did get on deck, Dad was laid on the deckside, amidst all the rigging and wires. ‘Whatever has happened?’ I yelled, but Dad could not speak; he just pointed upwards. I helped him up, but he was trembling like a leaf.

Then he told me. We had drifted towards the bridge and, before he could lower the mast, it had caught the electric wires that pass over the river. It wasn’t long before the bridge was alive with people. Two ambulances from Goole came on the bridge; nurses and two doctors got out. What a commotion! We had put everyone without power – Goole, Thorne, Airmyn, Cowick, Snaith, Pontefract, Castleford and lots of places. The doctors would have us go ashore, so Dad and I had to jump in the coggy and go in the ambulance to be examined. The doctors could hardly believe that we had escaped without being electrocuted or a burn of some kind. They asked Dad many questions, and the answer was – Dad nearly always soled and heeled our shoes and boots with rubber from the inside rim of a car tyre, and standing on rubber had saved our lives.

Another scare came when Billy was about seven or eight years old. We often took him with us on a trip if it was going to be a quick one and he was on holiday from school. He was not too keen to be on board; he didn't like the rough weather and rolling about. If it was calm, he was alright, but he didn't like the wind. He had been with us on a trip and we landed at Thorne Mill just on high water at dinner time. Some of his pals were playing about on the jetty and were shouting for him to come and play in the Mill. Dad and I went home after mooring the keel, and Billy said he would come later, when he had had a play.

Nearly half an hour went by, and he had not arrived, so I said I would fetch him for his dinner. As I got to the front gate, I met a little girl called Daisy Autherson who was running to meet me. Now Daisy was a very funny speaker who could not pronounce words properly, and she shouted, nearly out of breath, 'Tum twick, Tilly has tallen int' tivver'.

It took me a few seconds to understand what she was saying. Then I grasped it was, 'Come quick, Billy has fallen in the river'. Well, I simply flew to the Mill. Daisy’s Dad, Jack Autherson had managed to get Billy out, but he had Billy laid face upwards on the bank and was trying to get the water from him. I yelled, 'That's not the way to do it', and I simply picked Billy up and flung him across my shoulder, fireman's style, and ran as fast as I could home. Mum and Dad were very upset, as they thought I had gone to fetch him for his dinner. Dad rushed for the doctor, but when he came, Billy had regained consciousness. He asked who had pumped the water from him; we said 'No one'. But when we told him how I had got him home, and I was wet through on my shoulder and down my back, he said I had saved his life, as with running it had pumped all the water from his lungs. I didn't mind being wet through as long as Billy was alright.

Afterwards I asked Billy's pals what had happened, but they would not tell me and Billy couldn't, so we never knew what really happened. When Dad went to thank Mr Autherson for his kind deed, he said he did not know either; he had been having his dinner when he had heard screaming and shouting that Billy was in the water. After he had got into the coggy and pulled Billy out, there was not a lad in sight. That affair really frightened Billy, and it was a long while before he had another trip.

Waterside was a lovely community. Everyone knew everyone, and when Whitsuntide came, we all used to gather together and have a really good time. Mr and Mrs Wigley lived at No 2 in The Row, and they were on the religious side. They bought Mum’s old organ and made their front room into a place of worship. All the old timers used to gather there for chapel meetings, then discuss what was to be done for Whitsuntide. Mr and Mrs Blanchard had come to live at No 6 Quay Road, next door to us and he was a farmer. He loaned us the horses and three or four carts, and all the Waterside people collected money from raffles, jumble sales and tea parties, etc. then bought crepe paper of every colour to decorate the drays and carts in the most beautiful manner one could imagine.

My Mum and I made hundreds of paper flowers – roses, tulips, chrysanths, daffodils, and lots more. She taught all the lady members how to cut the petals to shape, how to curl the edges with a knife or the scissors blade, and how to twist the wire stalks so that they did not unwind. We had some beautiful decorated carts, and the prizes for the best were usually voted Waterside First, Second and Third. The procession used to leave Waterside about One o'clock, then paraded around Thorne, up one street down the other, meeting up with others from the various chapels and joining up with the Moorends group. The procession was nearly half a mile long, as Waterside entered as many as seven carts, the Wesleyan Chapel three or four, the Methodists three or four, the Congregational Chapel a similar number, then Moorends had five or six. All these carts stretched out with the school children who could not get on the carts walking behind. It made a long, long procession. They all collected in the Market Place to sing, then on to the Green to sing again, and finally landed at Foster's Field to finish off the singing and judging. What a Whitsuntide it was! We were so pleased when the time came to jump on the carts where we could; we were so tired we nearly fell asleep on the way home. It is a great pity that coloured snaps and pictures could not be taken then. Pictures of the carts would be beautifully coloured.

In June or July, Thorne Show would be held in Foster's Field. Things of every description would be on show – needlework, crochet, knitting, painting in oils or watercolour, dressmaking, even patterns made entirely of beads. My mother used to make rugs and carpets of nothing but silk stockings. I used to draw a fancy pattern on hessian, then dye the silk stockings to match the silk flowers on the pattern. The stockings were then cut into a strip about an inch deep, starting at the top and going round and round until one reached the heel. This was rolled into a ball, then pulled through the hessian with a crochet hook and left in a little mound on the carpet pattern.

There were also wedding cakes and bakery of every description and poultry, raw, dressed and cooked. In Waterside Row, a Mrs Lindley lived. She had one daughter, Maud, and two sons, Jim and Arnold. Arnold was a cute little lad, always laughing and full of fun. He had a nickname of 'Buzzy' but how he came to have it, I don't know. One day I saw Buzzy and his mother passing our house, all dressed up in Sunday clothes. Buzzy was nearly galloping and his mother had all her work on to keep up with him. As he passed I shouted to him, 'Hello Buzzy. Are you going for a walk?' 'No' he called back, 'Me Mam's taking me to the Show', and off he went running up the road, leaving his mother far behind.

It was past teatime when who should come running down the road but Buzzy. He was crying bitterly and I caught hold of him. His eyes were red and tears were streaming down his face. ‘Whatever is the matter. Have you been hurt or something?' I asked him. Then his mother caught up with us, and she was laughing like mad! Buzzy looked up at me and in between the sobbing he said ‘Me Mam promised to take me to the Show to see the dressed fowls’ – and the sobbing came again – ‘and there wasn’t even one with a frock on. They were all bare!’

In 1920 Dad asked me if I was able to look after the keel while he took Mum for a holiday. Mum had not had a honeymoon, and now with the family grown up, he was going to give her a real holiday, taking her to Belgium and Holland. Dad had already told Mr McKenzie, a great friend of his, and McKenzie (as we used to call him) had made all arrangements about the passports, cabin accommodation, the time of the boat leaving and everything. We had a few cats and hens at home, but Mrs Chester next door promised she would see to them being fed. So everything was set for the trip abroad.

Aunt Bertha said she would have Billy for company for her kiddies, and I was to stay in Hull with Arthur and Elsie going each day to the harbour side to see if the keel was all right. We had a good berth next to a coal hulk that never moved its moorings, so it was quite safe to stay alongside that. Arthur, his wife Elsie and I went to the Riverside Quay to see Mum and Dad off on the voyage of their lives and they boarded the SS Duke of Clarence.

I don’t know what Mum expected to see, but she came from the cabin and shouted to us on the quayside, 'What a cabin! It's more like a horse box'. Everyone around us laughed. I wondered if she expected it to be like the one on our Comity, all polished brass work and nice carpets. I know they are better equipped these days. But they would be only one night on the boat, as the 'Duke' was a very fast boat. They would be in Zeebrugge early next morning.

We used to hate to see the Duke of Clarence coming up the Humber, if we were moored at the Humber Dock lockpit, or near the harbour mouth, as she used to make such big waves. One could always expect a good swamping and a good roll after she had gone by. If we were broadside on to the huge wave behind her and were deep loaded, we usually had wet feet. We used to shout to the other boats, 'Fasten down. The Duke's coming up the Humber!'

Mum and Dad were away fourteen days; to me it seemed like fourteen years. We had never been parted for as long as that before, and I missed them terribly. I used to help Elsie tidy up, then I would get a tram for Salthouse Lane Bridge, walk down the harbour side to see that the Comity was all right, then walk as far as the City Square and get a halfpenny stage fare on the Hessle Road tram and go to see George, my eldest brother and Ada, his wife. I would stay with them for a few hours, sometimes run errands for Ada and fetch the kiddies home from school, then walk all the way back to Elsie's – about three miles, as our George lived at one end of Hull and Arthur the other. It was a tidy walk.

When Mum and Dad returned, what tales they had to tell! First of all, on arriving at Zeebrugge they were at a loss where to go, or where to ask for a hotel, so they told us they sat on the pier having a good look around at the war damage. Mum was worried and kept saying she wished she had never come! But Dad said, 'Cheer up. There's a chap coming. I'll ask him'. So as he drew near, Dad went up to him and said, 'Somewhere to eat and sleep'. He indicated this by putting his fingers to his mouth as if eating, then putting his hands to his head as if sleeping. Dad fully expected the man to be Dutch or Belgian and would not be able to understand if he asked in English. The man, however, gave a loud chuckle and said in broad Yorkshire, 'What’s up? D'yer want bed an' breakfast?' Well, Dad, Mum and the chap had a real good laugh, then he took them to a very nice place, and when they had made arrangements for staying, they had a lovely meal and then went sightseeing.

They brought lots of cards home showing all the damage done during World War I. They also had a picture taken of themselves dressed in Dutch clothes. Dad brought me a few trinkets, two serviette rings in mother of pearl, two fancy ornaments and a couple of lovely wall pictures – one of the promenade in Ostende, the other of the Kursaal Ostende. They shine beautifully as they are all inlaid with mother of pearl. Mum and Dad kept us amused for hours, telling us of the many things they had seen. Awful damage had been done during the war, but how happy the Dutch people were, and how pleased when they could tell amusing or sad tales to anyone like Mum and Dad who were on holiday.

Talking of the war time reminds me of an incident that happened one lovely sunny, hot day. We were drifting down the Humber to Hull, and Dad thought he would be able to take a short cut across Whitton Sands, near Brough. He was hoping for a little breeze to help us along so that we would not ground. That little breeze did come, and Dad felt sure we would make it, instead of going around the South channel which was a long way round. As we neared Middle Whitton Lightship, we cut across the main shipping channel, but the ebb must have been lower than we expected, because just as we got opposite Brough, we grounded on a sandbank, and within an hour we were high and dry.

Dad said that as long as we were there, until the tide turned we may as well scrub the keel's bottom. So he got the hold ladder, buckets and brushes, and over the side we went on to the sand. I had to keep running to the water's edge for buckets of water while Dad scrubbed the keel's bottom. The water lowered very quickly and I had further and further to go each time. On my way down to the water's edge, I used to pick up shells or stones, looking at them to see how pretty they were. Sometimes I collected a few lucky stones. On one trip, I noticed a stone with a hole in it, so I left the bucket near it while I took a full one for Dad, then went back to the stone which was partly embedded in the sand. I scraped the sand away round the stone, putting my fingers in the hole to wedge it up. It began to move and at last came free. I held it up, stared at it for a moment, then let out a big yell. It was a human skull; I had my finger in the eye hole! I flung it as far as I could into the deep water, then ran up to tell Dad, but I was so shocked or scared, I could hardly speak. He said, 'Good Heavens, lass. You look as if you’ve seen a ghost!' 'I have', I replied, and I told what I had seen. He went to the water's edge to see if he could find it, but I had thrown it too far. Dad said he would have taken it to Hull Police Station. They might have discovered whether it was a lost airman, or someone who was missing. I never forgot that incident.

Another time when we were aground on the sand, Dad and I sculled to the edge of Reed's Island, which is a massive island opposite Brough. Dad took his gun, and we expected to get a shot at a duck or a goose. The geese were very wary and would not come within gunshot range, but the ducks were not so timid. That day, the ducks did not come near us. What did come however, was a very big seagull, and as we were behind a piece of jutting land, he did not see us until too late. Dad had a pot at him, and we sculled out to get him. It took all my strength to try to lift it into the coggy, and Dad had to help me. When we did get it in, I took hold of one wing with one hand, and with its body on the coggy seat, I held the other wing out. Its wingspan was three or four inches longer than my arms outstretched. What a whopper it was! It had a massive beak, and Dad said it was an Albatross. When we went back, our keel was high and dry, so we had to walk up the sand leaving the coggy. Dad fetched a thin rope which he fastened to the coggy, and the other end on board the keel so that, when the tide came, it would not float the coggy away from us.

Around 1922 to 1924, a new Humber Bridge was proposed, and the people of Hull were asked to give their views on it. Most keelmen and river workers were against it, and my father had me write a letter to the Government, protesting against the bridge. He had nearly all the keelmen and tugmen who used the Humber every day sign a petition, saying that the proposed bridge would be a certain death-trap to shipping up and down the Humber. The fast flowing tides used to move the shipping channel, first to one side of the Humber, then sometimes down the middle. If abutments and pillars of a great size were used for the main archway and smaller ones for the smaller arches, the Humber itself was going to make navigation very difficult. Although the large arch would be over the shipping channel one day, the following week it would be over a sandbank while the shipping channel would be under one of the smaller arches. A letter came back asking Dad to visit London to see some big gentlemen in Government to explain things more clearly. So Dad and a Mr Rustling, a ship's husband, went to London to point out the dangers of the bridge.

Nothing more was heard of it for many, many years. Then it was brought up again, and talked of for many months. Eventually an idea was proposed to build a bridge of one single span, reaching across the Humber from the Yorkshire side to the Lincolnshire side. This was to be the largest single span bridge in the world, which when completed, would carry traffic of every description. The bridge was completed and actually opened on the 17th of July 1981. It was marvellous for me to be able to travel across the bridge. I could see for miles both up and down the Humber.

In the years 1919 and 1920, an airship was being built at Howden, near Goole. In fact, two previous ones had been built but with a disastrous start. First the R34 had crashed on the hills around Guisborough, but the crew were unhurt and had managed to get the airship up again on two engines and flown her back to Howden. Then the R32 was built and completed, ready to take the air. She would not rise, and after many attempts, it was decided to dismantle it. It was very bad news that two successive airships were failures. But later on, another airship was designed, the R38, at that time the biggest airship in the world. That would be around the year 1920. It made great news in the papers, and in 1921 it would be in flight. Later it was said that the airship had passed over Howden on its way to another air station.

Later it was reported in a local newspaper that, weather permitting, the R38 would set out on a long journey across the Atlantic to New Jersey, and would pass over many towns before taking the direct route. Hull would be one of the last towns the R38 would fly over – but she was destined never to reach New Jersey.

We were moored up the harbour, near the old hulk, not far from the harbour entrance. Everybody was standing around in groups waiting for the R38 to come sailing through the skies. At last the people began to shout and cheer, as along a clear blue sky, the airship came gliding along, flying low over the town. She was a beautiful sight, and shone like silver in the sun’s rays. She turned towards the Humber, which perhaps was as well, because all of a sudden, her nose pointed down as a great cloud of smoke or vapour engulfed her. She appeared to break in two. Everybody gaped, astonished at what they saw. We were all open mouthed, wondering what on earth had happened as one end suddenly began to fall, and bright red flames came from the middle. Then two terrific explosions shook the air and the airship came down, a mass of flames, at the mouth of the harbour, not far from the Minerva pier. It was a terrible sight and only five or six were saved out of a crew of fifty. I shall never forget the sight of that airship, sailing along in the sky shining like polished silver in the sunshine, then the next minute a broken mass of flames showering into the Humber. Everyone was stunned; it was hard to believe. My brother Arthur sculled to the mouth of the harbour to see if he could be of any help, or pick up any survivors, but already tugs were on the scene only to find that the parts of the airship had already sunk. Afterwards, when it was eventually salvaged, pieces of aluminium from the airship were made into memorial tokens and sold at sixpence or a shilling each to help the wives and children of the doomed men who had perished in the disaster. I have one of the aluminium tokens myself.

In March 1926 a disaster shook the town of Thorne. I had a cousin, called Maria after my mother. She spent a lot of weekends with us at Waterside. My aunt, her mother, had quite a large family – eight in all – and Maria she enjoyed being at Waterside. They had only a small house and she felt 'penned in' as she called it. She got to know a boy called Charlie Walton, and it was not long before they were married. They were devoted to one another, and came together to see us often. They had been married nearly ten years before news came that she was expecting a baby. After that crochet needles were never still.

When the baby arrived, everyone was delighted. It was a girl; Maria called her Betty, a lovely name for a lovely baby. Three years later there was a terrible accident in which six men, working in the new colliery shaft, were hurled to their deaths. What a shock it was for all of us when news came that amongst those killed was Charlie, our very dear cousin’s husband, and another friend John Reed. Maria and Betty could not be comforted, they had been such a happy couple, always together and always smiling.

Time passed quickly, and in 1930 we had a terrible winter. High winds nearly blew the buildings down. The rain came; all was flooded. The river overflowed and the fields across the river to Fishlake were just one big lake. Then came the frosts; everything was frozen with ice eight to ten inches deep. Dad said that he would not go to Hull for any cargoes so we had a nice stay at home. The Delves were a lovely skating rink, and people went on them every day. All the fields to Fishlake were covered with the thick ice. We could skate all the way there.

One lovely day, Emma Jackson and I put on our skates and had a good time on the ice as about twenty or more young men came and joined us. Among them was the Holt family. I knew two of them as they were keel people. Rustling was the eldest, then Horace. We used to see quite a lot of each other when we were all moored in Hull harbour. Rustling used to ask me to go out with him, but I did not like him enough. Well, while we were skating, the lads had got up a game of football and they asked Emma and me to be the goalies. What a game we had! They couldn’t kick the ball very well with skates on, and I used to pick up the ball when it came to the goal and throw it back. Another member of the Holt family came to me and said I must not pick up the ball. His name was Edgar. I told him that a goalie could pick up the ball, and we became friends. I eventually saw him quite a lot, and we got going out together. I liked him very much and we used to go to the cinema together. I told my Dad about him, and he said that he was a nice young man. So we kept up the friendship for two years, when he asked me if I would like to be married. I said yes.

The little cottage attached to Mum and Dad's house became empty, so Edgar and I decided to take it, paying Dad nine pence per week rent. Edgar went to work at Stanilands Boat Yard, and his weekly wage was £3 ten shillings a week. Dad bought a lovely fireplace with oven from Ross of Hull and put it in the cottage. It was a lovely stove in black and chrome. We decorated the cottage, wallpapered, whitewashed and painted it and made everything look nice. We also bought the furniture; as money was scarce we paid weekly for the bed and bedroom suite.

When we went to the Vicarage to make an appointment for the wedding, Canon Littlewood said that he could not marry us on Easter Monday, the day we had chosen, because he already had three weddings arranged for that day. So we had to wait until the next day, Easter Tuesday, and it turned out to be worth waiting for as it was a glorious sunny warm day. We did not go away for a honeymoon; people did not think about them in those days when there was less money about.

Trade to the Mill had dropped, and Dad was getting old by now. He decided to give up keeling and sell the keel now that his Mate was married. So that was the end of my eighteen years as a keelgirl.

Published by Thorne Local History Society

Supported by Thorne Moorends Regeneration Partnership

2014