The information presented is there to be used and enjoyed but please be sure to

acknowledge the source and author if you use any material.

Thorne Local History Society

The Steers Family Of Thorne - Cynthia Finch

Thorne and district Local History Association

Occasional paper No 25: 1997

In St. Nicholas Church in Thorne, there hangs a framed translation, given in 1987 by the late well-known entomologist William Bunting of Thorne. It tells us that the boy king, Edward VI in 1553 appointed 'our beloved Edward Stere' and twenty or so others, to be responsible for the care of the church. His namesake 'Edward Steers', my husband's uncle, died in 1989 at Quayside, Thorne and so I decided to find out about those in the family in between. After visits to various archives, I discovered that people bearing the name Stere and its variants, have lived in the Thorne area for a long time.

The Steers family of Thorne

Thorne lies in the south-easterly part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, and is bounded by Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire. The local rivers, particularly the Don, would have dominated the lives of the inhabitants of Thorne from a very early age. The place name evidence suggests a link with the thornbush which is growing profusely to this very day. The Latin translation is spinetum (sharp spikes) which is confirmatory. The marshy ground ensured slight isolation and the main mode of transport was boats. Records were kept by the various lords of the Manor of Hatfield Chace. These were called the Manorial Court Rolls, and from these I found an entry, dated 1342, referring to an inquisition which states that 'John Roke took the boat of John Stere against his will' and 'used it for his damage of 4 pence'. It seems probable from other entries, that this family, among others of course, were using boats of their own design to carry peat from the moors. It was used for fuel and even for constructing makeshift homes.

During the 14th century the Steers family owned land and appear on the list of families paying 4 pence Poll Tax to King Richard II in 1379. John Stere and his wife, Agnes, would have been summoned to attend perhaps by a notice on the door of the church. The Court of William de Warren, Lord of the Manor, was held at Hatfield, but manorial courts were held in the rest of the member of townships of the manor i.e. Thorne, Fishlake, Stainforth and Dowesthorpe.

During the 14th century the population of Thorne was about 200. These people would enjoy partaking of the fish and fowl which were abundant in the wetlands; and of course raised areas were put to agricultural. They grew wheat, barley, rye, peas and beans. Lavender was also grown. They farmed their own cows, sheep and pigs.

Thorne stands on a sand and gravel ridge and there appears from the records to have been a two field system in operation. The North and South fields were very extensive; the rest would be too wet for farming purposes. We can imagine the local inhabitants using stilts and passing on their flat bottomed boats. They would cross marshes on cleat boards, which were wooden soles secured to the feet by a leather hoop. In the History and Antiquities of Thorne published by Whaley, we read about a fisherman's house called Steere's lodge, standing on ground raised about, 4 feet above the ground often 'drowned'. This house, we believe, was at Holten Bridge latterly Hollins Bridge at Hatfield Woodhouse. The occupants may have been related to the Agnes Stere who was fined 2 pence for not doing work between Tweenbridge and the Severals in Hatfield. Ditches and drains were dug extensively and there were roads between all villages.

In 1400 the Court Rolls say the Constable was a certain William Stere and that he, together with his jury drawn from the locality, caused offenders to make good the roads. Some were accused of baking bread and brewing ale when they should have been attending Court. However the custom of the Manor may have protected tenants to a large extent because the jury itself was composed of local people.

Chosen men would meet in the vestry of the church to decide what crops to grow. As the church was close to the first cultivated land it is fair to assume that houses would be situated mainly in the area of Church Street and the market place. During the time that land was being allotted for cultivation in the 15th century, we can read from the Thorne records that Richard Clerk surrendered a toft with a cottage on it; a rood of land, an acre of moor and three and a half acres of waste land with 'appurtenances' (belongings?) in Thorne, to the use of John Stere and his brother Richard. An interesting footnote is and their heirs forever'. These premises were granted to John and Richard by the custom of the manor. The lord received forty pence for entry fine, plus another six pence from John Stere for one acre and one rood of meadow at (Spryingpursshe?) Thorne. I can only guess whether the meadow may have been part of the Ashfields which is mentioned in the local history books, because they grew hay there which was needed to feed the animals during the winter.

Some of the animals may have had to be killed if there wasn't enough hay to keep them alive and healthy throughout the whole of a bad winter. However, the family I am concerned with has managed to survive to this day.

There was a steady growth of population, but there were setbacks and reversals; the records suggest that about one third were affected by the Black Death. Although red deer and swans were owned by the crown, the monks of Roche Abbey were granted the eels by William, Earl of Warren. We gather they benefited from one tenth of the eels from fisheries in Hatfield, Thorne and Fishlake, so perhaps the local people procured just a few. The various lords of the manor owned demesne land; they would pass small strips from one tenant to another. They didn’t own the land of the villeins or freemen. They paid an entry fine and then rent. Those who were unwilling to yield to the terms would no doubt be evicted on occasion but these appear to be few in number. A constable, who was elected annually, was also in charge of the pound where the cattle were kept, in addition to assisting at the Courts.

The pinfold was near to the spot where a house was eventually built by Edward Stere. He placed his initials, a coat of arms and the date 1573 above its door. Edward was the eldest son of John who made his will in 1545. Edward inherited two thirds of his father's land and was named executor with his mother. Elisabeth (Elizabeth), John's wife, was to have all her own lands that had come to her from her mother. So we can safely assume that Elisabeth had come from a relatively wealthy family.

John, in his will, had asked to be buried within the church of St. Nicholas at Thorne, before the Lady Choir door.

In 1558, the year Queen Elizabeth I ascended to the throne, John's widow, Elizabeth, in turn made her will just prior to her death. She gave an altar cloth to the high altar of St. Nicholas, and to the tithes and oblations 4 shillings. She left thirteen pence to the maintaining of the bells and two shillings for 'church work'. Her late husband had left their married daughter, Margaret Foster, one 'sterind quie' (a barren heifer) of two years old that 'goes in the Ashfieldes'.

So the family were keeping cattle which pastured on the Ashfields. Sir Richard Spencer, Roger Stere and William Foster, John's son-in-law, were witnesses to the will. It was approved by the Dean of Doncaster in 1546. Edward Stere, John's son, may have been married by the time his mother died, because she left his son, also named Edward, a calf. As a woman, the part of Elizabeth's will which I found most interesting, was her bequest of her 'girdills' (waistbands) to her two elder daughters. They each also were to receive a silver spoon. She made Cecily, her daughter, her full executor. Evidently the family kept horses as she left a foal to William Foster, her grandson. I like the item of this lady's will in which she leaves her eldest grandson a milk cow. She makes it on condition that he should give his sister Jane the first calf 'to increase to her use'. Another gift is to her friend, John Millinge. He was to have a bushel of barley.

Perhaps Edward, her son, was too prosperous to need his mother's help by now, because around this period he married Jane Bunny. She came from a very eminent family long resident at Bunny Hall in Newton, near Wakefield. Jane was the youngest child of Richard Bunny and Rose, daughter of Sir John Topcliffe, Lord Chief Justice in 1512. An entry in Dugdale's Visitation of Yorkshire, page 48, states that Jane received 40 marks from her father on her marriage to Edward Srere of Thurne (Thorne). Jane was buried at Thorne Church on 18th August 1587.

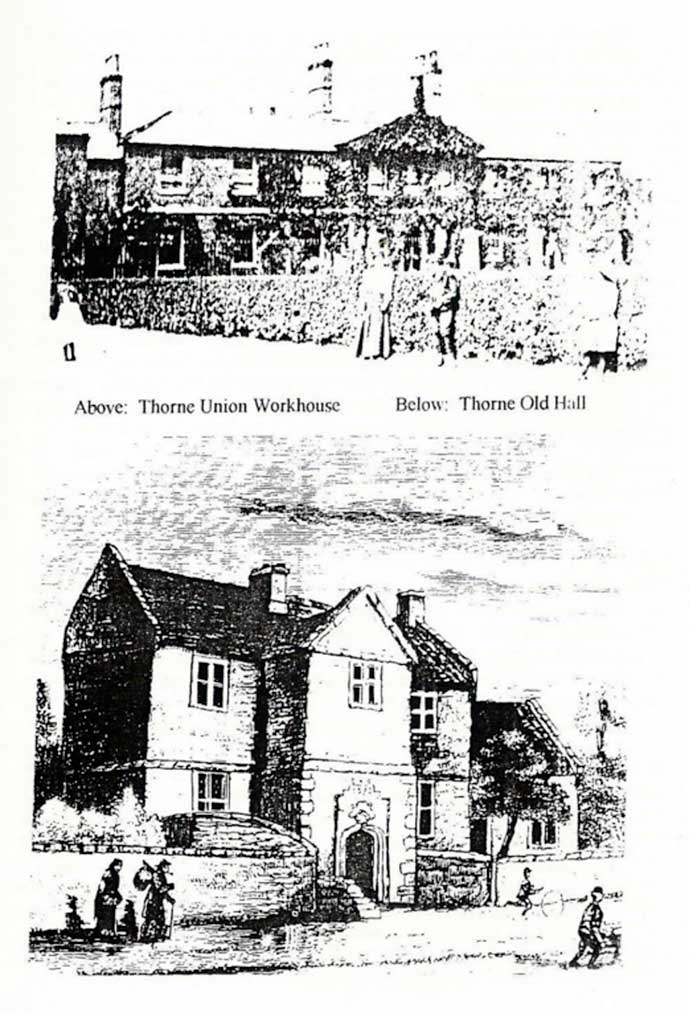

We believe that in the early sixteenth century the church at Thorne had been vandalised and the small castelet nearby is thought to have been used as a prison for offenders of the laws against poaching the royal game. When Edward VI intervened to help St. Nicholas Church, he stipulated that the local people may found a school. However he does not appear to have granted any money and none was forthcoming at that time for the education of the local people. Edward Stere, I regret to say, did not take the lead in this respect. He built his house in the area of Queen Street and what was later known in the twentieth century as ‘Dickie Fisher’s Orchard’. It was quite close to the Ashfields and is on an engraving in John Tomlinson’s The Level of Hatfield Chace and Parts Adjacent, 1882. Tomlinson describes an angular old hall with a curious porch. He thought it must have been a fitting 'home for gentle dames'. One most likely was Jane Bunny. How, I wonder, did she come to meet Edward Stere of Thorne? Would it have been at a ball or function, or had he perchance journeyed to Wakefield? They both died intestate, he in 1584 and Jane in 1587, having left a son called Edward. This is puzzling, but their deaths came at a time when research of the Bunny family proves them to have been on a downward spiral of fortune. As for 'Thorne Hall' as it is sometimes referred to, it is said that the dutch drainage engineer Cornelius Vermuyden, stayed there. It later became a home for the very poor. Later, of course, a Union House or Workhouse, was built. This may have stood in the grounds of the Old Hall; they were in the same area of Thorne. The story goes that the building was transformed into a beer-house called the 'Blazing Stump'. Malt Liquor was sold to boat hauliers. After Edward Stere had died, his goods were granted to his widow Jane and an inventory was exhibited. The person acting on her behalf was a certain Phineas Broket. Edward Taylor, her nephew, was a bondsman together with a Francis Steare. The name sometimes now has the new spelling. This may have been necessary because the branches of the family were increasing.

The first will I had found, that of John Stere in 1545, had been witnessed by a Roger Stere. He may have been a brother to John. Roger himself became 'sice in body and good in remembrance’ in 1557 and consequently made his will. Roger, I think, was not as rich as his brother because he now leaves ten shillings each to five sons; goods after that are granted to his daughter Margaret. His wife, Dorothy, has to have the customary third share. Women were seemingly treated quite fairly, or perhaps the third had been hers in the first place, left to her by her family and was a right. Thomas the son, perhaps the youngest, was left the older of two bocces’ (woods?) and his father’s 'fowling Geare'.

During the time of these wills, the population of Thorne were still enjoying the natural food resources abounding in the area. People bearing the name Stere were buried in the parish church of St. Nicholas. In 1558 the tithes from the church had been granted to Bess of Hardwick, Countess of Shrewsbury by Queen Elizabeth I. There was pressure on the church authorities to keep proper parish registers by now and Thorne acquiesced.

In the Public records for the year 1614 a man called Robert Whitehead was the keeper of King James I's game and deer. Sir Francis Bacon, Attorney General, acted on the crown’s behalf in a case. Francis Steare was involved, also assisting the King. In this document, cattle etc. had been straying on to the 'chace' and been impounded. The owners, presumably from the Manor of Crowle and its area, had to pay for their livestock's release. The case was postponed until 1620 because the King was considering enclosing the area with a view to raising money for himself.

John Tomlinson, writing in 1882 about Hatfield Chace, documents a letter which gives insight into the environment that the townspeople of Thorne inhabited:- It was dated 24th August, 1614 and was written by Gilbert, Earl of Shrewsbury to his wife. He says that he went to Hatfield at five o'clock in the morning, accompanied by his two nephews, three Markham brothers and six men of his own. He did not know where they were going until they were within five or six miles of Hatfield. At about eleven o'clock he killed three stags with his bow. He then goes on to say that he lodged at 'Steere's House'. This may have been the old hall in Thorne which was pulled down in 1860. Or perhaps it was the fisher's house in Hatfield Woodhouse which stood on stilts and was often completely flooded. Piecemeal work had been going on throughout the middle ages, draining the area. Commissions were issued to the Archbishop of York, Benedictine

Abbot of Selby, and also the Warrenns and Mowbrays to drain and protect, levy taxes and employ labour. Nothing had been done about draining the area so far. Efforts of sewer commissions were entirely directed to slowing down the flooding. De la Pryme, vicar of Thorne 1700-1704, writes that one Mr. Laversack suggested to Queen Elizabeth I an elaborate plan for draining Hatfield Chace, but nothing practical was done.

Then in the year 1626 Cornelius Vermuyden obtained his contract with Charles I to drain the area now known as the Levels. The Dutchman, on completion of the work, was to receive 'one full third of the recovered lands'. Up till that time Thorne people had paid their dues to the crown. King Charles, however, always short of money, sold the manor of Thorne to Vermuyden. George Stovin, the 18th century writer, states that a Thomas Vavasent became the 'solicitor' and took up the case. He spent part of his estate in defending his neighbours' rights. Cornelius Vermuyden undeterred, stopped up the course of the River Don, running by Thorne, with a great bank. This ran immediately beside the house which Edward Stere had built in 1573. It is possible that this caused the family upset and financial loss. The houses and grounds of inhabitants in Fishlake, Stainforth and Sykehouse were flooded at this time.

We can only begin to guess at the consternation of the local townspeople and the legal battles dragged on for years. Sometimes the clashes caused deaths. One of the conditions of the transfer of land to Vermuyden and his business associates was that previous tenants should keep their profits from the turf moors and the turbary. The ways to the moors also should be maintained. Sir Cornelius had to have the right to cut turf on one thousand acres of moors. Some towards Crowle and Sandtoft to a lesser degree. Any ground sown with rape was allotted to the tenants. Vermuyden was to hold them until after the time for gathering in the next summer. Any rents for the new enclosed grounds called Thorne Ings or Middlings lying near Haynes Hill were not now to be paid to the crown.

In 1632 William Stere made a will and asked that his body be buried in the churchyard at Thorne. He made Roger, his son, his executor. Probably Roger was by far the oldest of his children, as he was to have the 'messuage' (house) where William was living. I assume William was a widower as no wife is mentioned in the will. The house is said to have ground belonging to it and has highway into Kings Street through John Meggit's ground. In another item, William bequeathed one rood of land in the North field and one and a half acres in the South field. There was fishing over the moors as well as an acre of land. These he leaves by Robert Stephenson, tenant of the Lord of the Manor of Crowle. His daughter Catherine was to be given a black cow as she was just a child. His grandson was left a mare and a foal. Granddaughter Elizabeth Kirkbie was to be the recipient of a two years old calf. It is puzzling to note from the parish registers that between June and October 1632 there were ten burials of people of varying ages all called Stere. One wonders at the cause of so many deaths.

Hundreds of Dutchmen, Belgians and, of course, the Huguenots, came over from France to settle here to farm the reclaimed lands. John Stere's son Gervaise died aged only nineteen years. Had his mother been French?

Land had been redistributed in the Thorne area by 1631 and local tenants were awarded one hundred acres of land in the ‘Severalls’, Hatfield area and one hundred in the 'Ditchmarsh'. These later became the names of two farms. A list headed 'Feofment' implies Cornelius Vermuyden and John Gibson are agreeing to land for Edward Stere, Nicholas Taylor, John Starkie, Robert Foster, Henry Poole and Roger Portington of Hatfield.

When John Stere, yeoman of the parish of Thorne made his will, he named Anne, his wife, his full executor. A daughter, Elizabeth, received forty shillings, whilst her younger brothers shared that amount. Four younger sons of John were left 3 shillings and four pence each. No mention is made of a house, but Francis, another son, was to have two bay horses, two colts and a little foal. An interesting postscript is the fact that two fishermen, Robert Dewye and James Chancie, were given six pence each for helping with the will. In that year an entry in the parish register of St. Nicholas refers to the burial of 'Old Edward Stere gentleman'. The parish clerks often made a brief remark of their own. The curate at Thorne Church between 1640 and 1645 was Christopher Arngill. In a legal document he was given the care or tuition of Edward, Cornelius, Francis and William, the four teenage sons of Edward and Elizabeth Stere (both now deceased).

In 1642, according to the local history books, Sir Ralph Hawsby intended to march to the Isle of Axholme to protect the interests of the King. The Dutch ordered the flood gates of Snow Sewer to be pulled up, causing floods. Sir Robert Portington had a troop of horses quartered at Tudworth for several weeks. He is said to have attacked Sir Thomas Fairfax in 1643 as he passed through Hatfield Chace. Charles I was beheaded in 1649 and Oliver Cromwell was in power. But in spite of all the trouble, and as a result mainly of the drainage, agriculture was thriving in the area around Thorne. In 1658 Richard, son of Oliver Cromwell, granted a charter to hold a corn market in Thorne every Thursday. Thorne kept a copy of the Hearth Tax and there were several names on the list of rentals, the first being Edward Stere. Others in the family were George, Joseph, Roger and a woman called Marg. Stear.

Round about this time the Poor Law records included a bastardy bond. Joseph Stear, who was a private soldier of Hatfield, is named in one. John Tomlinson in his book tells us that there was a messuage or dwelling place near Thorne Churchyard called a college which may have gone to decay before Abraham de la Pryme was minister.

During the latter part of the 17th century there were many more floods. The parish registers state.

'1681 a great flood with high winds did break our banks in several places and drowned our towne upon Sunday at night, being Jan. 15th'. Gymes which can still be located, were scoured out. Some became fishponds.'

Abraham de la Pryme, the famous diarist, was vicar of Thorne from 1700 to 1704. He gives us a wonderfully clear picture of one of those great floods. The Thorne Parish Church register records it thus.

'1697 13th-15th Dec. a great flood, ye highest that has been known, broke ye banks in many places.'

The vicar, Abraham, relates that snow on 17th Dec. was ‘about two and a half feet thick after a pretty hard frost. After thawing it froze again for several days. Then when it finally thawed, the flood came roaring all of a sudden about 11 o’clock at night into Bramwith, Fishlake, Thorne and other towns. The churches rang their bells backward (as they commonly did in the case of a great fire). This frightened everybody'. He continues 'It came with such force against all the banks about Thorne which keeps the water off the levels', and that 'the water was so deep that many people were kept in the upper parts of their house, so that they almost pined. Their beasts were drowned about them. The oxen were bellowing and the sheep bleating'.

The loss hereabouts was said by our churchman to be more than a million pounds. The problem of the water was not really solved until the electric pumping stations were installed recently. People living at Waterside in the 1930s often had to move upstairs to avoid the water. Frequently a boat had to take them away to dry grounds. This was because the Black Drain could not get via the Warping Drain into the River Don.

When we examine the baptisms in the register of Thorne Church, it is noticeable that the addition of 'Gent' after the Steer fathers’ names is becoming less evident. Instead, by around 1700, they are being given as 'boatman', 'mariner', 'keelman' or carpenter. It seems that they were gradually losing their property and land. In 1704 William Brooke, a tanner by trade, bequeathed 'one messuage, late Steers', and some land to found a school.

Royalties and rents which are recorded in the Wakefield Manor Book tell us that the heirs of Thomas Brooke, Gent, could collect two shillings and sixpence for a house in the possession of Thomas Warburton, while for another house 'in the churchyard, Thorne, in the possession of Michael Stears' another two and sixpence was to be collected.

Many men would be working as Keelmen now that the rivers became available for more navigation. The keels were flat-bottomed, and to give them a grip of the water, lee-boards were adopted from Holland in the 17th century. These massive pieces of wood suspended from the vessels’ sides gave them stability and power to manoeuvre in open waters.

Before the Stainforth and Keadby Canal was cut at the latter end of the 18th century, more than forty families still made a living in cutting and preparing the peat which they transported by means of their peculiar boats to the River Don.

On a burial stone adjacent to the main gate of Thorne Church, we read of the untimely death in 1716 of Agnes, daughter of William Stear, at one year and eight months. This burial, strangely enough, is not recorded in the transcribed parish registers. However, on a happier note, the marriage of Joseph Stear, junior, mariner, to Frances Abbot, took place on 26th January of the same year. His father, Joseph Senior, died in 1736, aged 72 years. The gravestone is still clear enough to read and tells of the death of his daughter, Frances, in 1738. Certain branches of the family were still prosperous enough to be able to buy gravestones. Also they were liable for Constables’ Rate Assessments of two pence in the pound. In 1731 Joseph senior paid one shilling and a halfpenny while John paid five and a half pence and Thomas Stear is down to pay two pence. The following decades saw the building of many houses at Waterside, about a mile from the centre of Thorne. William Stear the waterman, mentioned in John Simpson’s book of 1784, may have lived there. The other Steer deserving inclusion is Joseph, the farmer. Jane lived to a good age; she was found dead in 1796, aged 68 years.

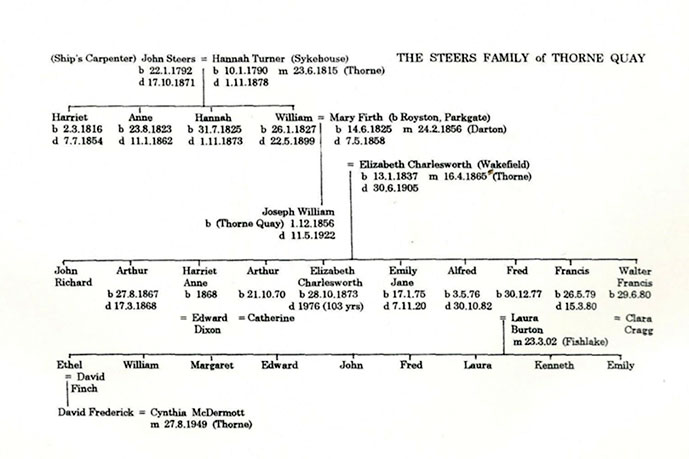

By the turn of the century the population of Thorne was about 2,600. At the time of the Hatfield, Thorne and Fishlake Enclosure Act, 1811, the number had risen to 2,713. One of those who died in 1800 was John Steer who had worked as a currier. He probably prepared animal skins by stretching and treating them ready for the shoemakers (or cordwainers). He may have been the father of my husband’s great great grandfather, also named John. The latter married Hannah Turner from Sykehouse on 23rd June 1815. 1812 saw the Rose's Act begin; this meant that special books for parish registers were to be properly preserved, there being penalties for false entries.

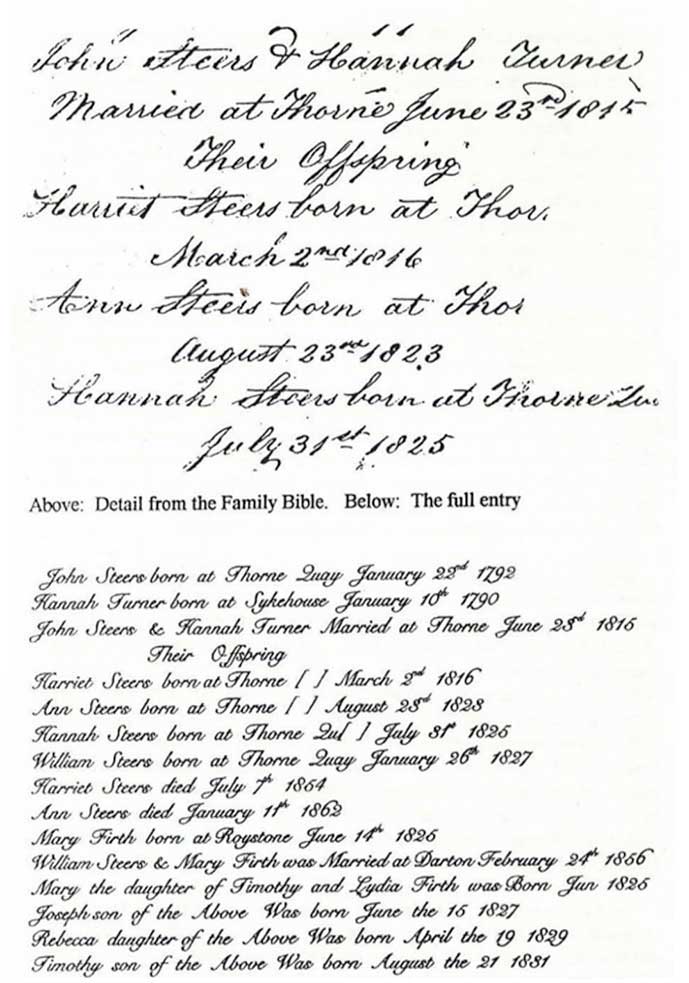

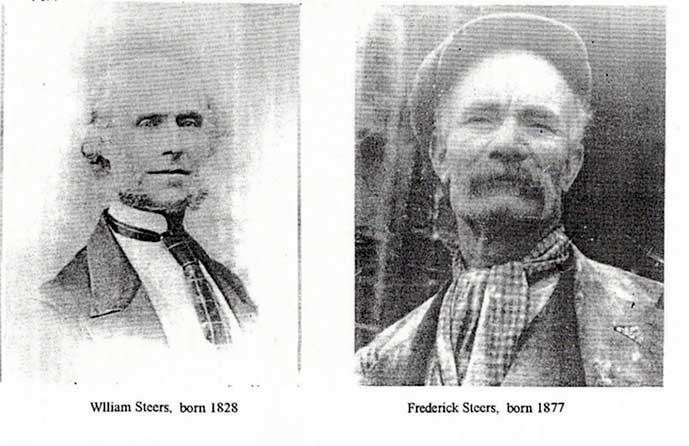

In the 1820s there were a series of bad harvests and one third of the farm labourers in England were out of work. The workhouses were allowed two shillings and sixpence for each person sent to them. As wages would be about ten shillings per week or less, this would seem quite an adequate sum. In 1834 the Union Workhouses were introduced and records had to be kept. Union Road in Thorne is so called after the Union Workhouse built there. In 1841 the first census was taken and many people were still not able to read or write. Mary Firth had been born in Royston, near Sheffield, in 1825 and received her bible when she was ten years old. She married William Steers of Thorne Waterside at Darton on 24th February 1856. She brought the bible with her when she came to live at Waterside after the marriage.

Alas she only enjoyed the area for two years as she died when her baby was born. Mary's bible, printed in 1835, as in many families, was used to record the births, marriages and deaths within the Steers family. Her own immediate family back in Darton had their births recorded on part of one page. Mary had been the eldest daughter

William, her husband, writing in a beautiful copperplate hand, records his family’s important events. One sad entry reads ‘Mary Steers departed this life on May 7th 1858 aged 32 years’ leaving a son, Joseph William, aged only 18 months.

John Steer (senior) and his wife Hannah (nee Turner) appear on the census taken in 1861 and John is still working at the age of 69 as a ship’s carpenter. Their son, Joseph William, is below them on the document, listed as a Rope Maker and Grocer; his son aged four appears as a ‘scholar’. William had opened a shop at Waterside which was by now a flourishing place of considerable trade. Whaley and Pearson were ropemakers, sloops were being built and paddle steamers launched. The Thorne Moor Improvement Company was formed in 1866 and turf or peat cut from the moors was sent from here to York, Hull and other markets. The young Joseph William would sometimes be able to see brigs unloading goods from London. His father may have witnessed the demolition of the House Edward Stere had so proudly built in 1573. The land, I think, had by now passed into other people’s hands. Building costs were relatively low and Henry Ellison, no doubt a descendant of John Ellison, a local boat builder, was able to live in what John Tomlinson describes as a ‘good family mansion with a well-walled garden, hot houses, lawn and shrubberies’. There were ‘convenient stabling, coach houses etc. a short distance from the hall’.

Perhaps I may be allowed to reflect a moment in envy of the natural beauty of certain areas of Thorne when I join the writer of ‘The Town of the Don’ Vol 22 1837;- ‘When I walked down by the river side from Thorne in the month of July, when the corn as beginning to change colour from the full green to the ripening brown; it was impossible not to be struck by the general luxuriance of the wheat and other crops. All along the banks, tall reed like grasses grow in profusion. The never-failing mugwort spreads so amply that it requires some perseverance on the part of the pedestrian to brush through it along the towing path. Occasionally, the wild celery or angelica, and common valerian, presented themselves among the herbage’. About the same year, however, John Salt reports in ‘Chartism in South Yorkshire’, ‘The local rivers froze allowing a sheep to be roasted on the Don’.

So now Thorne is emerging as a town employing all kinds of trades. In agriculture there was exemption from tolls in the market which had been granted in 1818. The Bawtry-Selby turnpike road was in use and it is fair to assume that people would be travelling to other towns much more widely than before. According to T.S. Williams’ ‘Early History of the Don Navigation’ 1965, letters were written by Sir J. Cooke to Joseph Mellish in London, suggesting an Act to make a navigable canal from the River Dun near Stainforth to Keadby. In 1793 the Act was finally obtained, and ninety subscribers enrolled. The canal opened in 1797. After this many new houses were built within the town of Thorne and the value of the property in its vicinity went up. This, of course, produced a market for local timber, not only for vessels, but for bridges, sluices and general canal maintenance. This called into being skilled workmen and we can see from the ten-yearly census forms that the Steers’ men often became carpenters and shipwrights. The ‘Thorne Directory’ lists 22 mariners. According to details from the ‘Victoria County History’ the population of Thorne in 1801 was 2,655.

In the parish registers for 1817, the overseers at Thorne were exhorted to bring ‘struggling seamen’ and ‘seafaring men’ below the age of fifty, in a state of health and ability, to the Justices at the ‘Angel Inn’ in Doncaster so that they could be directed to the King’s ships. Thorne was trading and there was a daily river service to Hull, connecting at Thorne with the daily coach from the expanding Sheffield industrial area. At this period Hull was a great port for the Greenland trade and large whalebones arrived here to form the gateway of Thorne Brewery. It is said that during the heyday of the quay at Waterside, a large proportion of the ropemaking gear had consisted of curved whalebone posts, supporting cross-bars with the tenterhooks through which the twisting threads passed.

William Steers married for a second time. His wife was ten years younger than he was and she originated from Wakefield. Elizabeth Charlesworth came to Thorne to be married to William Steers in the spring of 1865. Her surname was subsequently given as a middle name to various children when they were baptised. Her granddaughter, Ethel Charlesworth (my late mother-in-law) was named after her. The couple had ten children and William wrote their births and deaths in the bible his first wife had brought. Joseph the first son to the latter Mary Firth, had left the family home to live in Sheffield, returning to his mother’s roots, no doubt. He became a painter and decorator.

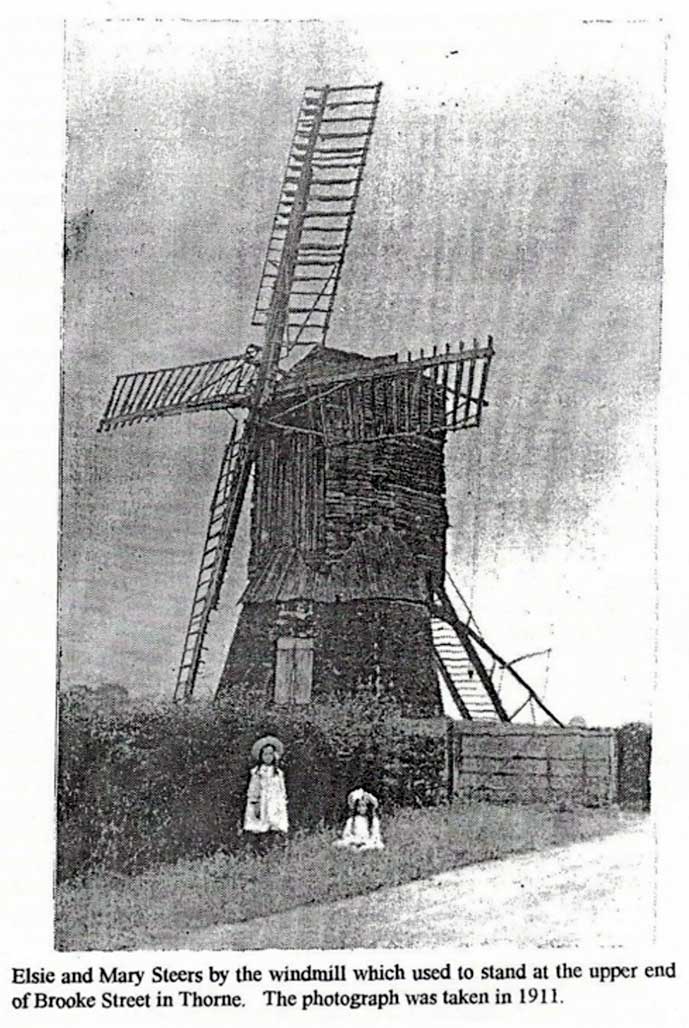

It is thanks to Joseph that we own a collection of photographs of Thorne and particularly Waterside. He was an amateur photographer and took innumerable snaps of his children. One is taken near the ropery where his father worked and shows family members sitting near what we called the ‘Granny Grunt’ tree. Elizabeth Steers, who remained a spinster to the age of 103 years, took sandwiches from Quayside along with tea in an enamel can for her father when she was a child. When interviewed by a reporter for a Doncaster newspaper in 1960, Lizzie said she remembered going to the tiny Wesleyan chapel which was built at Waterside about 1860 or before. She went there with her parents and there were always a lot of Dutchmen in the congregation. The shipbuilding had brought them over. Lizzie Steers closed the only shop in Waterside when she was 70 in 1943.

But Thorne Quay and its industries were well in decline and were almost annihilated by the coming of the railways. When they did come it was without an Act of Parliament, the line being laid alongside the canal by a contractor called Blyth of Conisbrough. In an article from the Doncaster Gazette dated 14th December 1855 it stated that ‘the initial section of the Crowle single line from Doncaster to Thorne was first brought into use on 11th Dec 1855, when a train of ten wagons arrived at Thorne Waterside with coal for a shipment to Hull’. Passenger traffic began at Thorne South in 1856. Thirteen years later, another station, Thorne North, was built to provide services to Hull. Gradually sailors and working hands transferred their residences and services to Goole, the port nine miles down the river. The canals were subsequently bought by the Railway Company, the original railway station being converted into a depot for the waterways. It is probable that at this time Thorne served all the needs of the local inhabitants and was relatively prosperous. By the end of the 19th century, the population was about 3,800. Some persons in vessels would most likely been included in the ten-yearly census as well as Waterside people.

One man who may well have been away from his home was the late Mr Pattrick from Waterside. His late daughter, Evelyn confirmed to me that her father ‘went captain to his mother’s keel ‘Hannah and Harriet’ of Thorne, Yorkshire February 15, 1892’. That was an extract from the first page of his diary. ‘Boat lebords two shillings’ is entered in the records frequently. His journeys took him to the Albert Docks in Hull and, I quote, ‘Grimsby for iron loaded it on the 9 Sept 1893 left 10 Sunday’. He states that he arrived 22 Sept at Sheffield, having sailed to Keadby and Thorne. Again, another entry ‘horst to Don – 7 shillings, horst to Mexborough 7 shillings, horst to Rotherham 7 shillings and horst to Sheffield 8 shillings’. The keelmen were very hard working and had a reputation for honesty. Theirs must, I imagine, have been a peaceful life.

About the same time a letter was written by William Steers living in the house adjacent to the warehouse on the quay at Waterside. He died in 1899 so we can assume that the letter was written on Christmas Eve a few years earlier. Although the time was 1.45pm, his sons were still unloading cargo from vessels. It was addressed to William’s daughters Elizabeth who would be seventeen in 1890; Annie was five years older.

‘My dear Annie and Lizzie,

I know you will be pleased to learn we received your beautiful hamper last night. Mother went to the station after work time and brought it home. You should have seen them all how pleased they were to see the contents. I had been wishing Father Christmas would bring me a pair of slippers so I am so far satisfied. I think they all are. Fred is so high up with his walking stick. I tell him I think I should have had it if it had not had his name on it. But I did not set him roaring as he sometimes says. What …. sent is beautifully nice. So kind of him and Mrs. Watson, also Mr. Duncon. Be sure to thank them all ever so much for what they sent. Emily is so busy. We expect them from Sheffield by the three train. Em. Is going to meet them. I am not well enough – such an awful cold, cannot keep warm in bed. We got a beautiful goose 10 and a quarter lbs. We do not know the price until they return from Doncaster.

Miss Weldrake has taken several geese, turkeys and ducks. Mr. Chester of Goole sent us a nice rabbit, so we shall be pretty well off. Boys and girls seem to enjoy what they eat. We hope you found the pork pie nice and enjoyed it. Em. is just putting onions in the goose. We don’t know what holidays the boys will have. They are busy unloading a vessel today. I expect they will have to stay at it until discharged. Perhaps it will be late. We do not know of anyone coming. I wrote to Arthur but could not to John. I was not well enough to do so. Your dear mother has poor nights. Last night she did not settle until two. The boys had to be up a little before six. I often think how thankful we should all feel to have her better again.

Some frost last night and it has been quite foggy today. Em. says I have not mentioned the grapes. I think you would pay a good price for them – such beauties. The cake looks so nice. Taken much of Emily’s time.

I must now draw to a close with all our thanks. We should all have liked you both here. With love and best wishes.

Father.

During the course of my research into the family of my late mother-in-law, I feel that I have come to know my home town better. The ‘Manuscript in a Red Box’ which is a novel based on fact, believed to have been written by John Hamilton, augmented my understanding of the lives of the people living hereabouts during the troubled period of the drainage in the 17th century. At other times ‘births, marriages and deaths’ lists provided my imagination with little. What does remain, however, is a kind of kindred spirit between myself and the locality, when I began to realise that the male line of this particular family has continued to live in Thorne for at least the last six hundred years.

Footnotes

I; E134/12 Jas/Mich 6

ii: 1779 Pr 1263 – Doncaster

iii; K W Grimes ‘Saving Yorkshire’s Square Rigger’ Beverley Guardian 11th Jan 1958

Local History Books on Thorne

1; Hunter. Doncaster County Library. A classic work

2: John Tomlinson. 1882

3: Abraham de la Pryme. Mss ed. Charles Jackson. Surtees Soc. 1870

4: W O Peck. History of Bawtry and Thorne

5: History and Antiquities with some account of Hatfield and Thorne. Publ. Whaley. 1829 (revised 1878)

6: White’s Directory 1862

7: David Nunn. ‘Kings, Canals & Coal’ 1993

8: ‘Manuscripts in a Red Box’ Hamilton (a novel)

9: Victoria County History

10: Thorne Directory

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all those people who have given me assistance, especially Mr. Reg Brocklesby and Maureen Hambrecht for translations, and Mrs Helen Boyd and Laurie Thorp for the typing of this study.

Published by Thorne Local History Society

Supported by Thorne Moorends Regeneration Partnership 2014

© Thorne Moorends Regeneration Partnership. All Rights Reserved.